The history of the Treaty House in Uxbridge was a story I was bursting to write, but just couldn’t bring myself to publish until I had what I needed to tell the story well. Originally, I expected it would only take a few weeks (maybe a month?) to do the research and get the story written. But that was much more than a year ago! This project has shown me just how stubborn I can be sometimes. But it has paid off…

If we were so misguided as to think of history as nothing more than a collection of dates, names and events, I wouldn’t describe it as merely uninteresting–I’d describe it as positively anesthetic! Why should we spend one minute of our own limited lives trying to understand the life of someone who already had their time under the sun? It’s a fair question. For me, the first answer is that I don’t believe anything is preordained. Quite often, whatever happened might have unfolded differently if some of the underlying factors had played out differently. Certainly, it’s not hard to imagine that the currently unfolding war in Ukraine would be going much differently if not for the unexpected solidarity and fighting spirit of the people and leaders of Ukraine.

My second reason is that generally, the “plays” of history are condensed into a general narrative focused on the primary actors and the outcomes of the “big picture”. Even if those narratives are entirely accurate, they seldom have the luxury of breathing life into the choices, character and outcomes of the lesser actors most of us would relate to. For me, grasping what it was really like in their time allows those long-dead actors to hold a mirror up for us to better understand ourselves and those around us. It allows the choices of those actors to provide lessons about the potential consequences of our own actions (or inactions). My favorite thought experiment is this: if we could travel through time and witness historical events like the Treaty Negotiations of 1645 for ourselves, how much of the scene would surprise us?

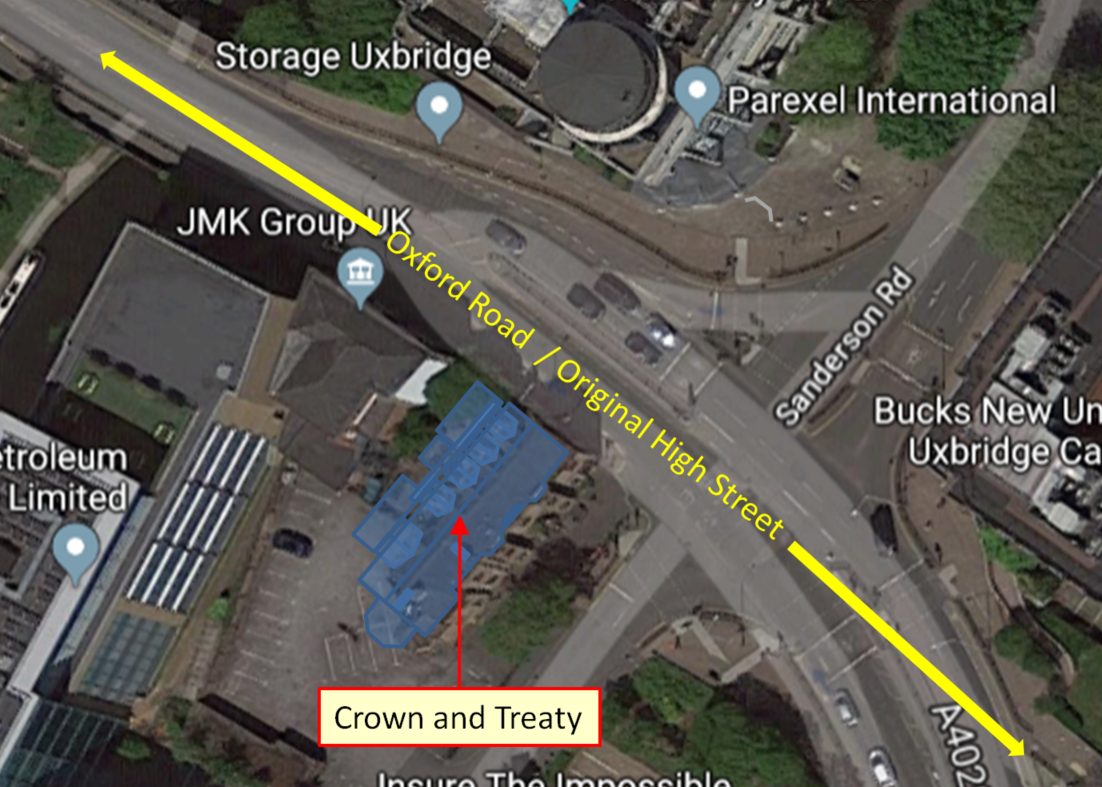

In the same way that my desire to have some idea what Sir Richard Lane looked like led me on a remarkable journey to find his lost portrait, my desire to comprehend the 1645 treaty negotiations through his eyes has led me to the mystery of the building that hosted those negotiations. And I discovered a surprise lurking in the details I found. The original Treaty House and its grounds were not just beautiful, they were grand. This property stood defiantly on one end of town, forcing the high road to Oxford to go around it. And to the royalist commissioners, it was outfitted by the peace faction of Parliament in hospitality and respect. It was provisioned in hope as thoroughly as it was in staples.

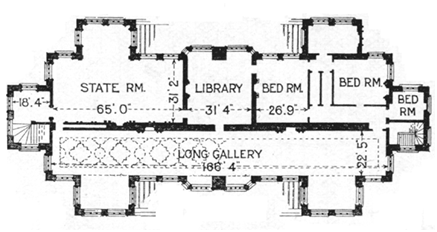

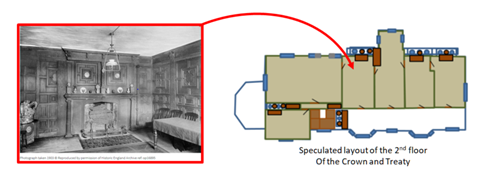

Despite how complete the existing Treaty House seems, historical records are clear that the building seen today was originally a much larger building. It’s also clear that the rest of that building was taken down long ago. Early on, I had hoped the room the negotiations took place in was still there. I would have loved to have stood in that space and imagined being there. It didn’t take long for me to discover this would not be possible, though. I soon found other records that make it clear that the negotiations room was in a part of the house that no longer exists.

Although disappointed, I was also hooked. I wanted to know more. I wanted to know what the original building was like. These negotiations were not some small meeting in the 1600’s equivalent of a corporate conference room. This event took months to plan, much more akin to a modern summit meeting in both size and importance. Each side of the negotiations was allowed 32 commissioners, but those accompanying the Royalist commissioners alone numbered around 180. The event lasted more than a month, requiring significant planning and care to decorate and provision the event for its participants. Try to imagine the scale of a room able to handle the large square table (approximately 16 feet on each side) that was built for the occasion. Then imagine there was space for a railing around it with additional seating beyond the railing.

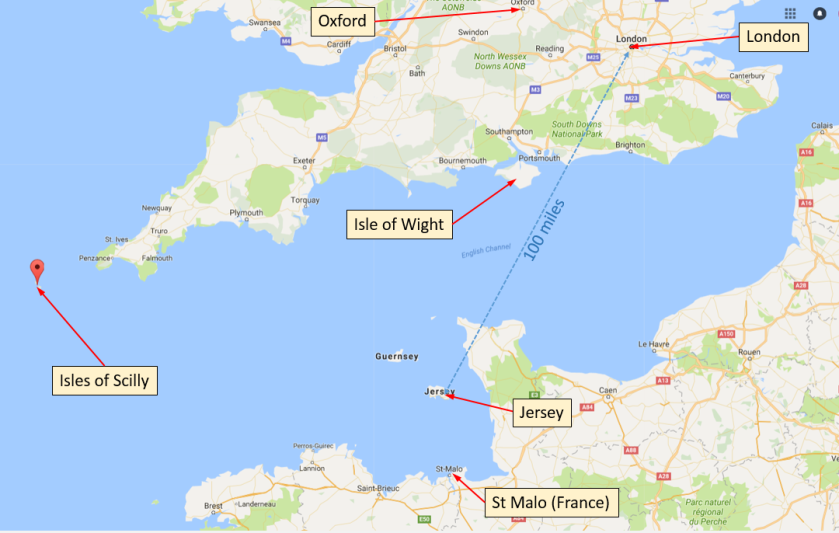

What were the thoughts of Sir Richard Lane and his colleagues as they travelled that road into enemy held territory that cold January? How were they treated when they arrived ? Despite the well-documented hospitality of their parliamentarian hosts, feelings ran high on both sides of the argument. For their security, the commissioners were allowed to carry their swords for personal protection. And what was the sight that awaited them as they walked in groups from the Inns at the center of town?

The stakes could not have been higher. If the negotiations had been successful, much of the pain of that era might have been avoided. Imagine if there had been no exile of Charles II and no execution of King Charles I. What if there had been no Commonwealth era and and no need for a Restoration?

But the royalist commissioners were also working for a much more personal outcome–reaching an agreement was their best hope of wresting their careers, families and very lives from the nightmare scenario of having remained loyal to an increasingly lost cause. For Richard Lane, a successful treaty would have allowed him to return to London not merely as a senior Master of the Bench of Middle Temple, but as Chief Baron of the king’s Exchequer Court, and personal advisor to the next King of England. Sir Richard would have been a much-remarked upon figure in the post-war era. His thoughtful and well founded understanding of the law and governance would have marked him among the most widely respected figures of his time. He would have returned to his family and home in Northampton in great favor, influence and probably wealth.

But that’s the version of history that didn’t happen. The peace negotiations of 1645 were the tipping point for Sir Richard Lane’s personal fate, and they were not successful. The war resumed. His family home and possessions were confiscated by a vengeful Parliament. Only a year later, Lane participated in his next negotiations–for terms of surrender for the king’s wartime capital of Oxford. Afterwards, Sir Richard Lane was punished for his loyalty to the throne by being forced into exile with the king’s heir, Charles II. King Charles I was captured, and after years of resisting pressure to compromise the “divine right of kings”, he was executed. For years, Sir Richard Lane served the impoverished ascendant King Charles II in exile as counsellor and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. He would eventually fall ill and die there, never having seen his family or his home again.

The 1645 Peace Treaty Negotiations were a happier tipping point for the mansion that hosted them. If not for its legacy of hosting one of the most important treaty negotiations in English history, the mansion previously known as the “Bennet House” would otherwise have been torn down in obscurity long ago.

The Search for the Original Treaty House

All I needed to tell the story of the Treaty Negotiations effectively was an image of the original mansion. If I could just locate one, I would wrap up the research, publish my article and move on to the next subject. It was easy enough to think so, but locating the image I needed soon became the deepest “rabbit hole” I’ve stumbled into yet!

The difficulty isn’t finding historic images of the Treaty House—there are many of them. If fact, those images tell a story of a building that has seen many uses, and has stood while many buildings around it rose and fell (including several buildings that were appended to the Treaty House itself at differing times). For a time, I thought I had even found the image I was after. But after months of studying, occasionally over-interpreting, and ultimately dismissing every image I could find, I realized something important: all of the surviving images of the Treaty House are of the existing building over time. It seems by the time even the oldest of these surviving images was created, living memory of the original structure had long since faded.

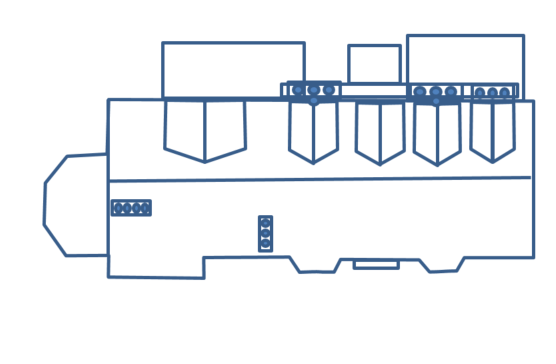

What has survived of the original house are a smattering of clues and descriptive mentions in various historical sources. I decided to see if I could leverage these clues to extend my speculative model of the original interior of the existing structure into a model of the entire original building. This was a time consuming but interesting exercise. Through a few iterations, it has yielded a compelling model that aligns well with the available evidence and architectural styles present in the existing building. Finally, with the help of a talented and historically inclined graphic artist, I now have the image I have sought: a remarkable sketch of the “reconstructed” Original Treaty House yielded by this model. And it is beautiful. I will share it in the next few articles, but we have some interesting ground to cover first.

Let’s start by unwinding a visual history of the Treaty House from modern times, through the Industrial age and backwards to the time of the middle 1600’s. Let’s get a sense of what has transpired since the time Sir Richard Lane and the other commissioners made their way through the spaces of what is now an elegant restaurant on their way upstairs to stop the war and save their king.

A Journey Backwards in Time with the Treaty House

The challenge with trying to understand the original form of a mansion that was built 300 years before the invention of photography is that buildings normally undergo changes over time. For instance, although the current structure is a natural and timeless brick construction, for most of modern history, the Treaty House was sheathed in a layer of white stucco. The brickwork was re-exposed sometime in the 1970s. The effort and care that must have taken is almost enough for me forgive the 70’s for disco…

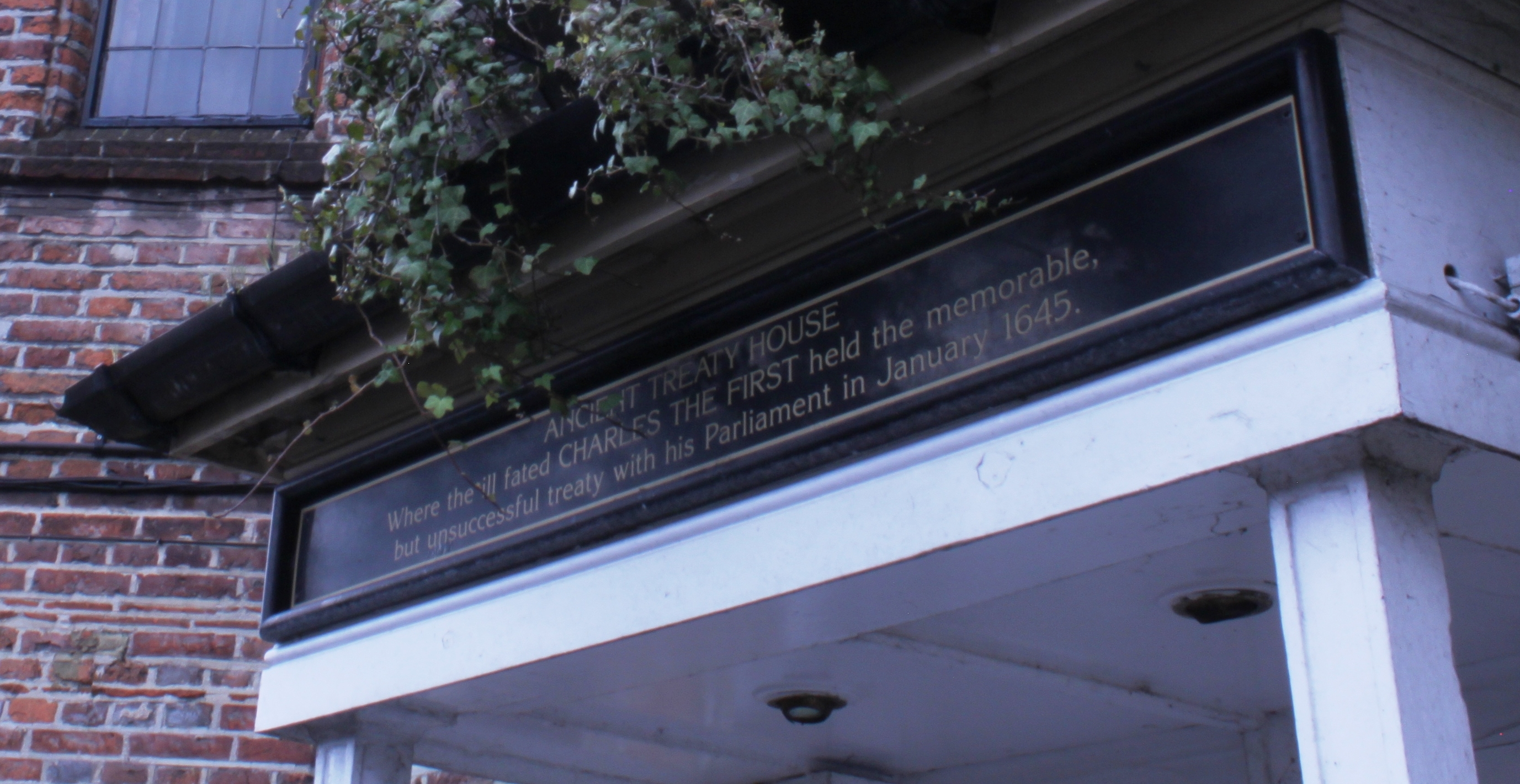

Modern street view of the Crown and Treaty (2018). The building sits at a major intersection in what can reasonably be described as a technology park.

Additional modern views of the Crown and Treaty (2018) for reference, showing all faces of the building.

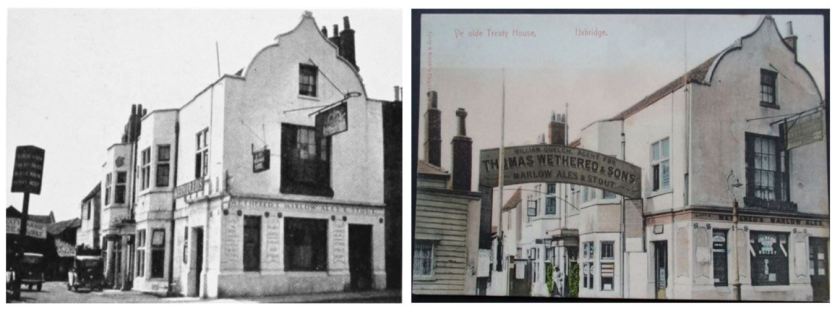

The Treaty House in the 1900’s

The next two images are photographs of the Treaty House from the early years of World War II. On the left is a photograph from 1937, and on the right, a colorized photograph from ca 1940. The most striking insights of these images are the closeness of the street alongside the building, the presence of an attached building along the face of the Oxford Road end of the building and the stucco covering the original brickwork. At the time, the main floor served as a retail establishment with the second floor used for living spaces. Note the presence of the second floor sign projecting over the Oxford Road calling attention to the structure’s historic role. An inspection of the modern images reveals that the this metal structure and an updated version of the sign survive to this day.

A unique photograph of the building from the early 1900s depicts the state of the rear of the building at that time. Its interesting to note that in the early 1900’s, the stuccoing had been removed from the non-street faces. This was a change. As you will see, the rear of the building was also also stuccoed in earlier times. The concrete structural repair to the upper floor wall at the right of this image. This concrete structural repair is still present today.

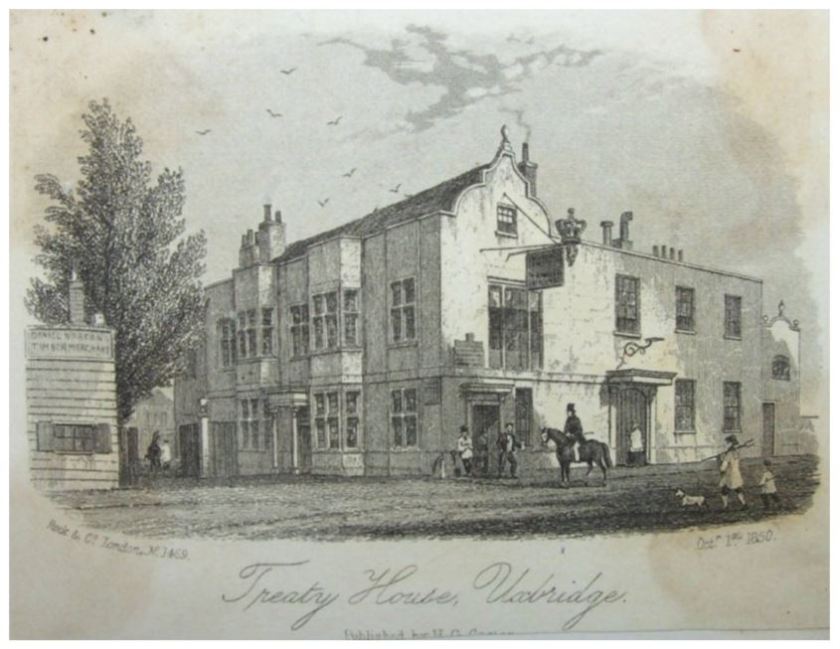

The Treaty House in the 1800’s

The time of the Industrial Revolution was also a time of great renaissance of historical interest in England. During this era (middle 1800’s), a great many historical articles were printed and accompanied by illustrations to support them. Thus, there are a number of interesting images of the Treaty House from this time. Some of these images are contemporary, while others were historical, based on older images.

In the carefully made image of the Treaty house (below) dated 1850, you can see a full view of the building that had been joined to the side of the Treaty House facing onto the Oxford Road. Notice the changing door arrangements on the Oxford Road face of the Treaty House itself. This image also reveals the purpose of the horizontal loop at the end of the metal sign that still overhangs the road—it once held a large decorative crown.

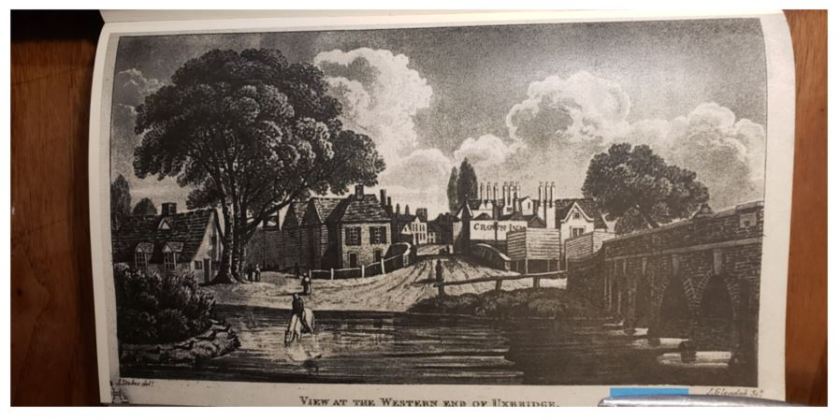

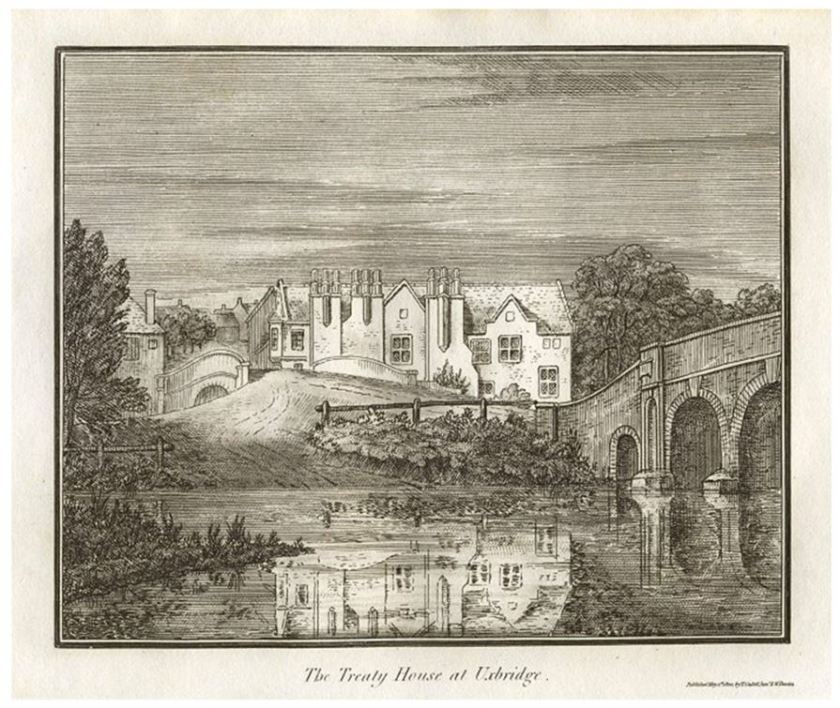

This next image is from the same general era. This view from the Colne River shows a ford crossing next to the historic “5 arch” bridge (at right). This foreground crossing allowed travellers who didn’t mind getting their feet wet to water their horses while avoid paying a toll to use the bridge. Just beyond lies a second bridge, over the Grand Canal. And in the middle distance, the Treaty House at a time the building was known as the “Crown Inn”.

There is one other fun detail worth mentioning in this image: can you make out a small sign with a white swan hanging from the tree in front of the small house at the left of this image? This was likely the descendant of the “Swan Inn”, which was on this site in the 1600’s. Remarkably, this business survives to this day (at this same location) and is known as the “Swan and Bottle”. When I am next in Uxbridge, I absolutely intend to buy a pint there as well!

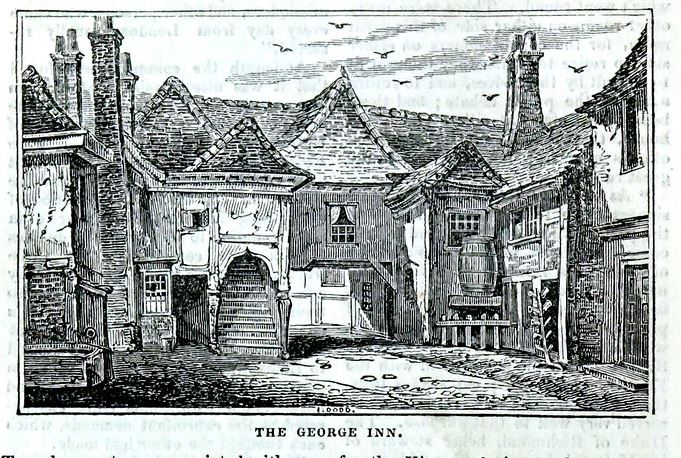

It should be noted that the period use of the name (the Crown Inn) for the Treaty House should not be confused with the “Crown Inn” of the 1600’s. This earlier Crown Inn was located in the center of town near the “George Inn”.

In 1645, this pair of Uxbridge inns sat somewhat symbolically on opposite sides of the street in the middle of Uxbridge. They served as the separate working headquarters of the royalist and parliamentary negotiation teams. Although it hosted the negotiations themselves, the Treaty House was a private residence at the time. It seems only a few especially important guests actually stayed there while the negotiations took place. The commissioners (of both sides) were quartered all over town, gathering at their respective inns to meet with their colleagues when the negotiations were not in session.

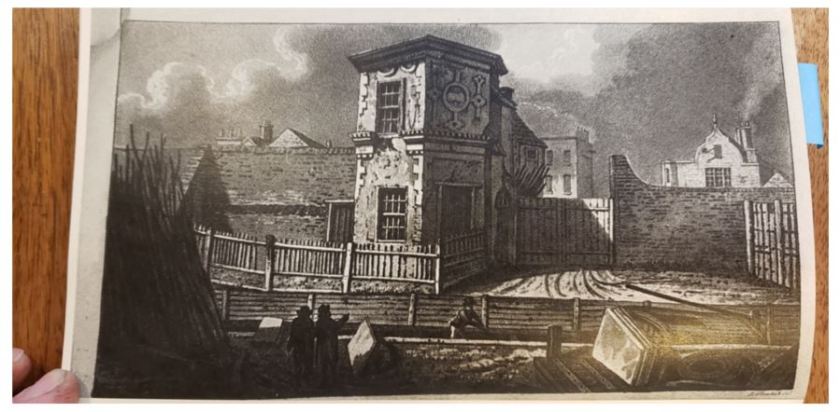

The next image worth discussing is of the Gatehouse (from Riches/Redford book, inserted at pp 64). This ornate and long-vanished gatehouse is believed to have been a remnant of what was originally an enclosing wall around the original Treaty House property. There are several surviving images of this fascinating scene that were clearly made at different times.

In this particular depiction, Treaty House in the distance is geometrically flawed, and therefore potentially inaccurate, in my opinion. For example, notice that the angle of the metal sign structure and the angle of the roofine are both depicted seeming to move to the right as they get further away, while the chimney line is depicted angling to the left as it gets further away. Also, the shape of the end face of the building is odd (and inconsistent with other depictions in this, or any other era). One detail that does seem credible is the disappearance of the elegant second floor bay window that once protruded over the Oxford Road.

To its credit, this image clearly explains something that is murky in earlier images this one was apparently based on–a foreground boat canal laid in what was (in earlier times) the bed of the original High Road as it ran around the Treaty House grounds. This is consistent with other records from the first decades after the Grand Canal was finished. By that time, the original property had been split and the Oxford Road had been diverted to pass directly in front of the end of the Treaty House (as it does today). After the Grand Canal was finished, a patchwork of minor “branch” canals were dug to allow canal barge cargoes to be unloaded directly in front of the many industrial buildings which had sprung up in the area. This part of Uxbridge had become an industrial center taking advantage of the place the region’s best water transport (the Grand Canal) and the best road transport (the Oxford Road) intersected.

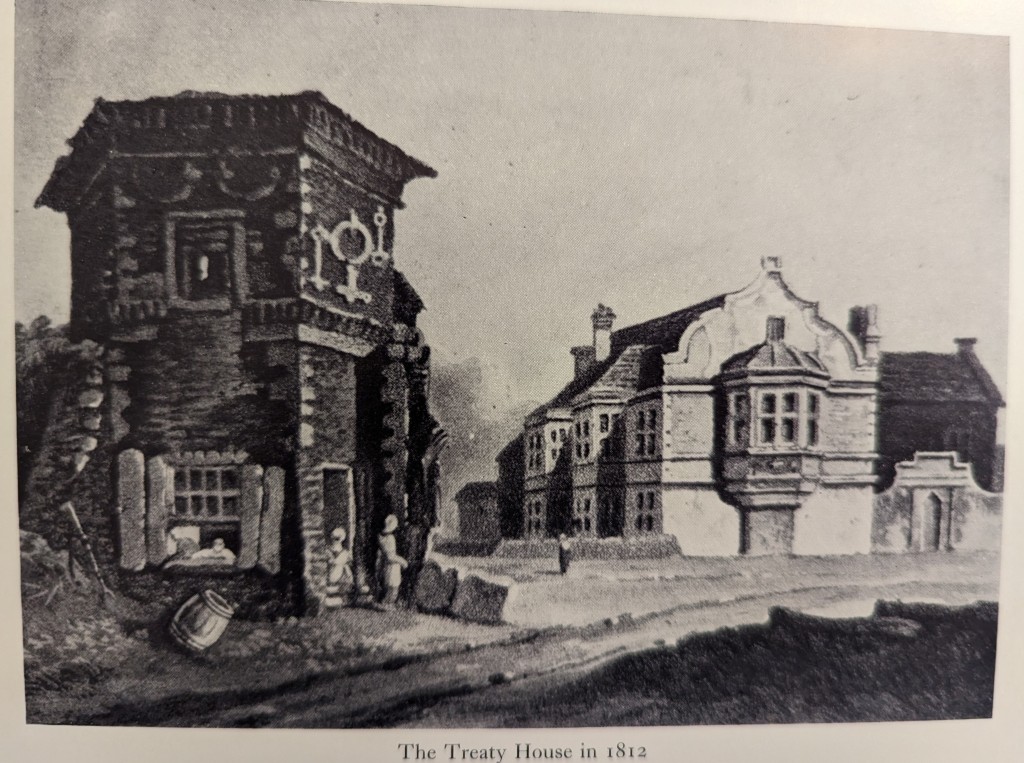

The next image is well done, and unique. This perspective provides a clear view of the second story bay window and many ornate flourishes that seem shared by the gatehouse and the Treaty House (which were originally part of the same property).

The fragment of wall on the right side of the gatehouse includes the vestige of a large arch rising from it. This probable fragment of a gate and the significant structure to the left of the gatehouse are evidence of a wall surrounding the original property. This makes sense. Such a wall would have been especially important for a property that lay alongside a major roadway.

This image is striking for capturing a number of ornate construction details which disappeared in later, more pragmatic periods of the building’s existence. This primarily includes the dormers above the bay window columns on the long side of the building, the elaborate plasterwork and graceful second floor bay window on the face overlooking the Oxford Road. While this wall was not original, both style and materials from the original house were likely incorporated when this wall was created to repair the severed end of the building.

I was particularly intrigued by the large structure that appears to be appended to the chimney wall of the Treaty House. This particular auxiliary structure is unique to this image. I have to admit this structure sent me on a significant tangent. Studying it, I wondered if the original image might have been from the middle 1700s and might have depicted the original form of the Treaty House. To evaluate this possibility, I created a conceptual model of the original building built upon that possibility. This model turned out to align with nearly all of the criteria from evidence I had gathered. Nearly all. Like Edison’s famous failed attempts to develop a light bulb, it was this failed model that let me to the correct one. In my next article, I will share these models and the form of the original Treaty House they revealed!

The Treaty House in the latter 1700s

Moving into the late 1700’s, there are only a few images available. The first is an excellent woodcut made from the perspective of someone on the far bank of the Colne looking back at the Treaty House. The presence of the bridge over the Grand Canal (which was finished in 1793), is consistent with the reported date of this image (1796). Looking closely at the left end of the building, you can see a second story bay window protruding out over the high road. On the right, note the absence of the hexagonal structure that later appears (and is present today) at that that end of the building.

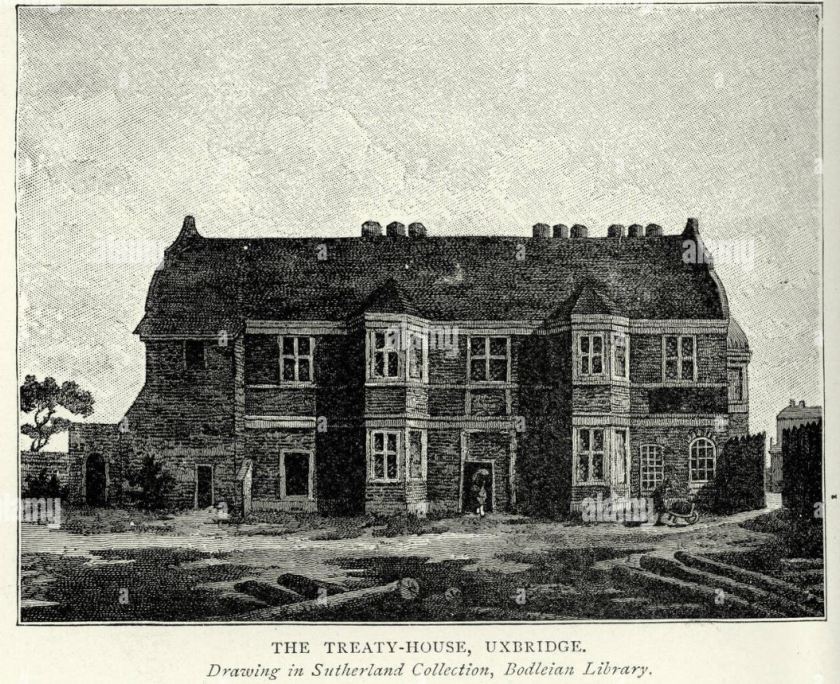

There are two final images that seem to be the oldest surviving images of the Treaty House. Both depictions are from a perspective looking at the windowed face of the existing building. Both show the Treaty House with a brick exterior, which would place them before the first stuccoing of the building as it appears in the 1796 image above.

The first of these images is an excellent depiction which I believe shows the Treaty House as in the decades after the main house and other wing were demolished, and before significant repairs eliminated many early details. This image (above) seems to show the house is a state of some neglect and hastily made repairs in the latter 1700’s. I will discuss this image in more detail in my next article, as it provides some surprising insights into the original form of the house–before significant repair and changes around the turn of the century and the 1802 remodel.

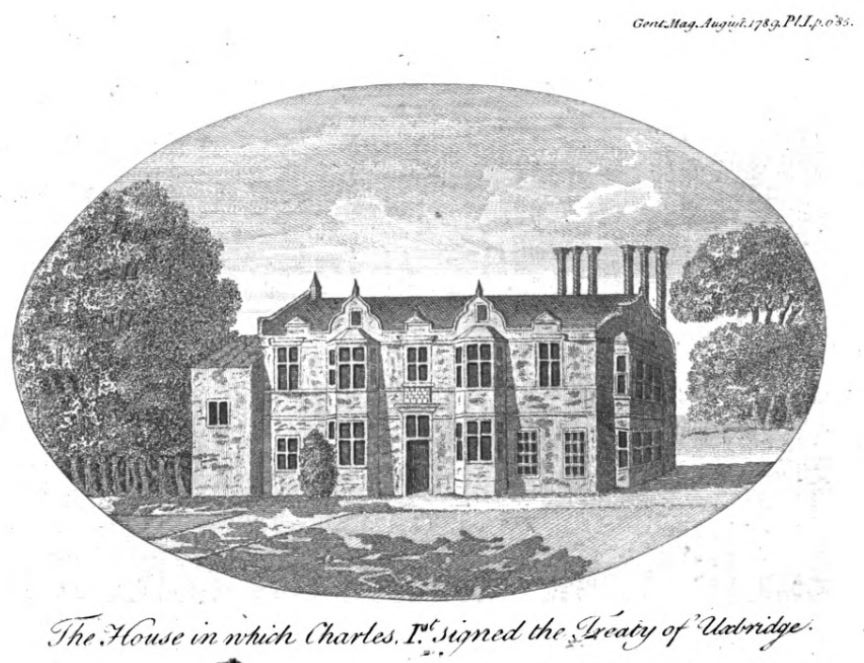

The other of these earliest images is an enigma. This depiction was not made from direct observation, as it has a number of glaring technical flaws no artist capable of producing the image would have made had they been looking at the building while making it. This image appeared in a reader contribution section of the August 1789 edition of the Gentlemen’s Magazine. I’d seen this image before, but had discounted it because of the glaring issues with the depiction.

The roof is clearly”flattened”, and the chimney configurations are completely wrong–only two of three sets of flues are shown, and they are not in the right locations. Because flues rise straight up from the fireplaces they serve, this configuration would have left much of the house unheated. The bay colum on the right face of the building is also a bit odd, with the depiction of that face seeming wider than the building actually is.

The other end of the building is completely wrong, also. What I think of as the “kitchen” end of the building is integrated under the roof in every other depiction, with an enlarged footprint that provides strength to that end of the building. In this flawed drawing, it appears as a nearly detached structure. Even the caption of this image is very much in error. Not only was no peace agreement reached during these negotiations (after nearly a month of negotiations the treaty was abandoned), but the king was never in attendance. In fact, there is no record indicating King Charles I ever set foot in the Treaty House.

What stymied me is why this image was made in the first place? The fact that it appeared in the 1789 edition of the magazine only establishes that the image existed by that time. It could have been in existence for many years and randomly submitted by whoever possessed it in 1789. And I think it was. The historical errors in the note published with the image suggest it was contributed by someone with limited historical knowledge.

After wrestling with this odd “splinter” under my nail, a scenario finally occurred to me that could reasonably explain the origin of this image. It is my theory that this was a “concept” drawing for what the Treaty House might look like after this still-existing wing was salvaged from the demolition of the rest of the house. Imagine a middle 1700’s developer meeting to discuss their proposal for the work, and providing a drawing to substantiate that the wing could be successfully converted into a coherent, stand-alone building. In this scenario, the exact details wouldn’t have been important. The artist could have reasonably sketched out the details of this wing before going back to a more convenient workplace to produce the final drawing. It also explains the idyllic, park-like setting around the depicted building.

If this theory is correct, then the unique depiction of the original door in the middle of the wing should be at least roughly correct. The stylized gables above the bay columns are unique among images of the Treaty House, but are consistent with other architecture from this period that featured such gables. Of course, these gables are not present in the latter 1700’s image, suggesting that the roof was redone and simplified either as part of the salvaging of this wing during the demolition or sometime in the decades after. Other information substantiates that the full height bay column on the Oxford Road end of this building was implemented after the demolition. This bay column was later amended to remove its lower half, possibly during the 1802 remodel. The the pair of windows on the ground floor at the right end of this wing seem to have been an original feature of the building, even though they seem to have been corrupted by piecemeal repairs by the time the “dilapidated” image was made in the latter 1700’s.

In the next article, I will be introducing the painstakingly produced reconstruction image of the original Treaty House!

I never intended to “take the Pandemic off” from writing, but it certainly worked out that way. I suppose most of us have had our priorities reworked by the historical dramas unfolding around us, so perhaps you understand. In that sense, I do hope this article finds you well!

Probably the most important of the diversions which have otherwise occupied my time is that Mary and I were married in February of 2021 in a classic “turning lemons into lemonade” story…

We were months away from a planned April wedding when new pandemic restrictions threw those plans into the ditch. So we made up a mischievous “Plan B” and married ourselves alone at the Summit of a 12,000 foot high Colorado mountain in February.

With the temperature reaching a high of only 5 degrees (F) and snow blowing around us, I set up a camera tripod with “snow feet” to capture the moment. Using the flowers as a wind screen, I had nestled a lapel microphone deep in the bouquet so the wind wouldn’t drown out our voices. We had tied our rings to our wrists with loops of satin ribbon so we wouldn’t lose them in the deep snow if they were dropped by numb fingers. Finally, I attached three cameras to the tripod because we had agreed there would be no “second takes”–we would either have the the video afterwards, or we wouldn’t. It was a good thing we did this because we later discovered that two of the three cameras had failed in the cold!

So in the end, our wedding was beautiful, exhilarating and achingly romantic. We were both on the verge of frostbite on our hands by the time we got our skis back on, but we didn’t care.

The fun part is that we didn’t tell anyone about it. They found out when we lowered a large video screen in the middle of our September “wedding” some seven months later. We giggled ourselves to sleep many nights preparing to drop that “bomb” on two hundred of our closest family and friends! It went over wonderfully. To paraphrase that great English philosopher (Monty Python, of course), ” We’re not dead yet!”.