As we got off the plane at Heathrow, I couldn’t have imagined the article about our first quick stop in England would eventually require many months to complete.

We had an important appointment at Windsor Castle later the afternoon we arrived. But the plane had arrived on time, leaving us just enough time to swing by Uxbridge on the way. There was something in Uxbridge I really wanted to see for myself!

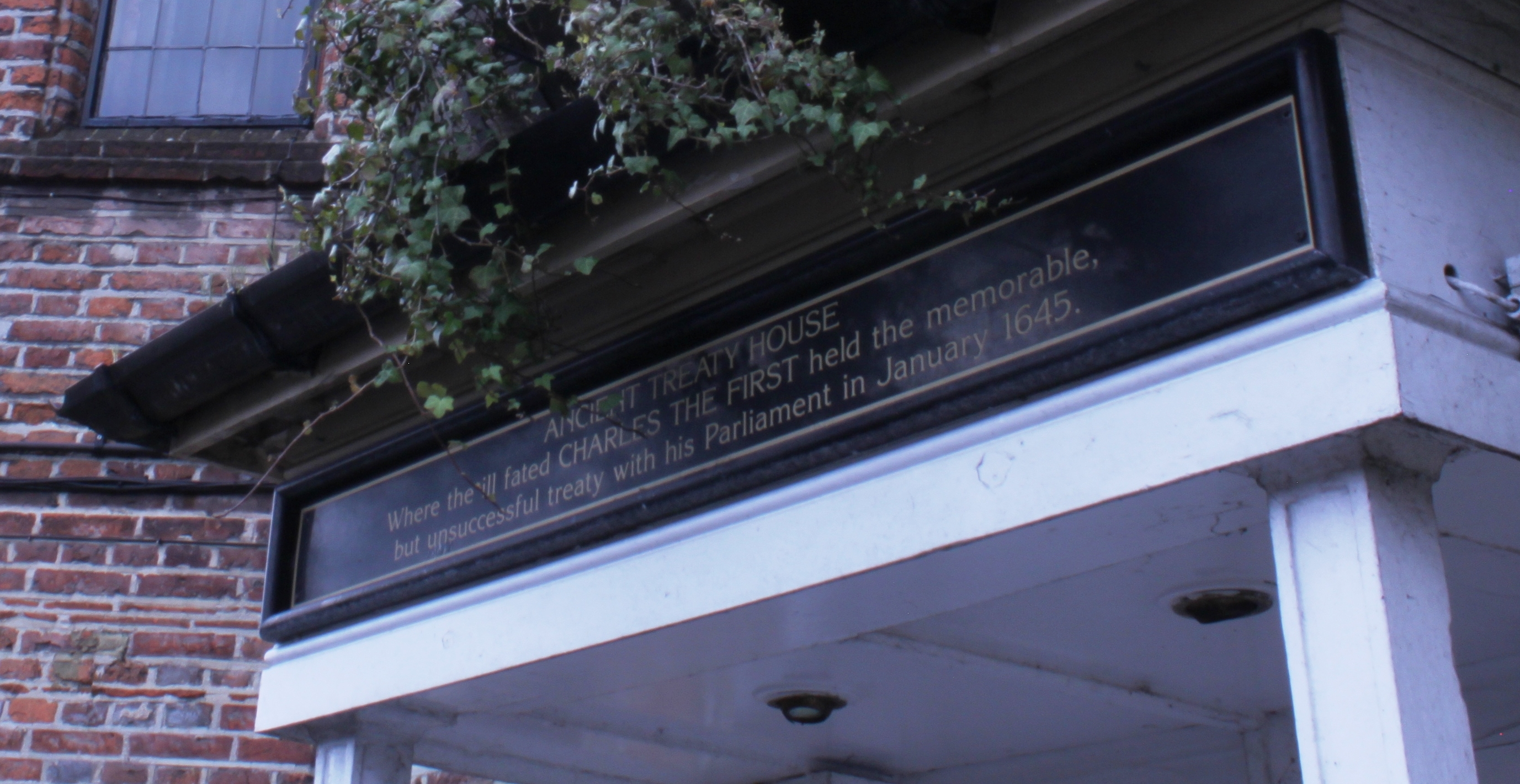

Hemmed in by a phalanx of glass-sheathed office buildings, and utterly out of place in a modern technology park, the “Crown and Treaty” is a gorgeous 500 year-old building perched precariously upon a bare vestige of its former ground. If time and circumstance have rendered this building a diminished but still graceful woman of age, my work over the last many months has revealed that it wasn’t always so. Nearly 400 years ago, when the newly appointed Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer Court, Sir Richard Lane, and the other peace commissioners walked through her doors, she was the spectacular and defiant diva who “owned” that end of town…

The Peace Treaty Negotiations of 1645

In the late Fall of 1644, Sir Richard Lane had been living in the packed royalist enclave of Oxford for two years while the English Civil war raged. This struggle to decide the fate of the “divine right of kings” versus representative government in England had recently begun to trend poorly for King Charles I. When the peace faction within the rebellious Parliament was able to win support for an attempt at a peace treaty, a truce was struck and treaty negotiations were planned. For a few months, both sides enjoyed a respite while arrangements were set to hold the treaty negotiations in the town of Uxbridge, partway along the road connecting the opposing war capitals of London and Oxford.

A large mansion on one end of that road-inn town was chosen as the negotiations site. Quickly provisioned, furnished and decorated to accommodate the gravitas of the occasion (and the large number of participants), this mansion would be afterwards known as the “Treaty House”. The historic importance of the treaty negotiations held there was remarked upon in an 1850 article appearing in “Gentlemen’s Magazine”:

By far the most memorable treaty on English ground, made or attempted to be made between a king and his people (Runnymede not excepted) was attempted at Uxbridge in the winter of 1644-5…

Peter Cunningham, Gentlemen’s Magazine, April 10 1850

For me, a chance to visit the “Crown and Treaty” (as it is known today) was a chance to walk in the place Sir Richard Lane and his fellow commissioners met as they struggled to find terms their warring masters could accept. I was curious to learn whatever I could about their experience. Where did everyone stay for the month the negotiations continued? What did they eat? How well did their accommodations keep out the February cold? How did both sides receive those close friends and former colleagues they found seated on the opposite side of the negotiating table?

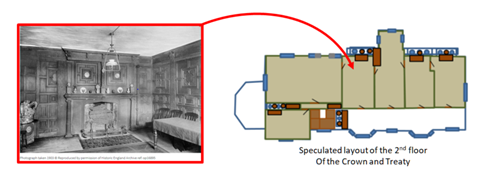

But I soon discovered that details about the “Crown and Treaty” are frustratingly sparse once you get past the few existing summary articles and exterior photographs. I was unable to locate a floor plan or any description of the building’s historic layout. Excepting only a few grainy vintage photographs of an upstairs room referred to as the “presence chamber”, the scant interior photographs I was able to find were anecdotal shots of pub tables on the modern main floor. In 2018, the enigmatic 500-year-old Crown and Treaty had become the stately but beleaguered home of a struggling local pub and small band venue.

Of course, a good pub and small band venue is one of my favorite things! If we could make time to stop by the Crown and Treaty—and if they were open—I would love to sip a pint of their best local ale while absorbing everything about the building around me. And if I was lucky, perhaps the proprietor would be willing to give me a brief walk-through of the building!

Unfortunately, this was not to be…

Visit to the Crown and Treaty

Arriving at the Crown and Treaty straight from Heathrow, it didn’t take us long to discover the building was locked, and no one was around. Making the best of it, we set about photographing and studying the exterior of the building.

A short while later, we noticed a small group of people gathered at the front door. We introduced ourselves and discovered we were talking to the new owner of the building and a group of young people planning to assist in an upcoming restoration. Despite my rising hopes, it soon became evident that the previous owner (who was supposed to arrive with the key) was not going to show up that day. Ah, well! We enjoyed meeting them, and perhaps someday we will be able to return and have that pint and a meal amid their handiwork. I recently read that the Crown and Treaty has since re-opened as a fine new restaurant.

Later, as my research into the building’s history progressed, I realized it wouldn’t have made much difference if we had been allowed in. Although it would have been fascinating to see in any case, I now believe the room where the negotiations were held has not existed for more than three centuries.

Unraveling the Enigmatic History of the Crown and Treaty

The existing accounts consistently indicate that today’s “Crown and Treaty” was originally part of a larger house. Regrettably, those accounts consistently suggest that the room in which the 1645 peace negotiations were held was likely in a portion of the house that no longer exists.

Of course, someone less obsessed would have let it go at that. But I became intrigued by a scattering of clues I’ve encountered in my research on the treaty negotiations. Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle strewn across a table, I had the sense that much more of the seemingly lost history of this English historical landmark was within reach, if I could just figure out how these scattered clues fit together! How could I resist that? So, I clicked on my headlamp and dove headfirst into this latest “rabbit-hole”!

“Reconstruction” of the original Crown and Treaty Floorplan

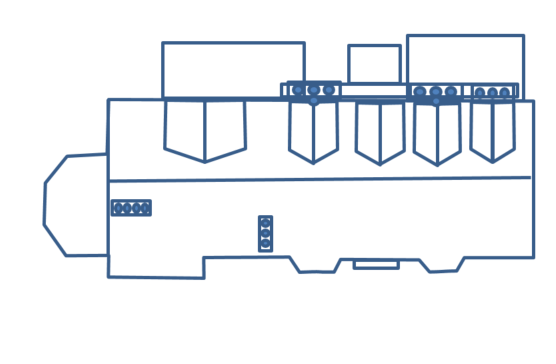

Using a combination of photographs I had taken and overhead imagery from Google Earth, I was first able to construct an overhead building plan of the Crown and Treaty (below). From this, I obtained a rough measurement for the existing building: 80 feet long and 30 feet wide (approximately 24.5 by 9 meters). The existing windows make it clear that the building has 3 floors of usable space: 2 regular floors and an attic/dormer floor.

Chimney Analysis

Among the most striking features of the Treaty House are the majestic array of chimneys along the building’s back side, and the equally beautiful array of windows across its front. As I contemplated what could be deduced about the interior of this building, I realized there are some timeless rules of construction that could tell me a great deal about the interior based on these features:

- Windows that face the South are best for gathering heat and light into the rooms behind them

- Where they exist, interior partitioning walls connect to exterior walls between windows

- enclosed spaces are easier to heat selectively

- generally, every significant space in the living area of the house will have at least one source of direct heat (and in the middle 1600s, the only reasonable source of heat was a fireplace)

- each fireplace will (generally) have its own chimney flue

- chimney flues do not follow complicated paths—they generally rise directly (or nearly so) above the fireplaces they service

- in a space large enough to require more than one fireplace, the fireplaces will generally not be located together

Looking at the pictures of the Crown and Treaty, it’s clear the majority of the flues (11 of them) lie along the back wall of the house. By the rules above, this means that all of the 11 related fireplaces must lie along the back wall as well. Given how tightly grouped these flues are, it became fairly clear that the eastern half of the building’s back wall must have been dedicated to a row of bedroom-width spaces on the first two floors, leaving a couple of flues for fireplaces in the attic level.

With a building depth of 30 feet and following the (incorrect) mindset that the house had been built as an inn (with lots of rooms–a purpose it served in later centuries), I assumed the back rooms extended to just less than half the depth of the house. But this left me with a problem: where were the flues for the fireplaces needed to heat the opposing set of rooms I imagined lay along the front of the house? It was clear there was an important architectural design consideration I did not yet understand.

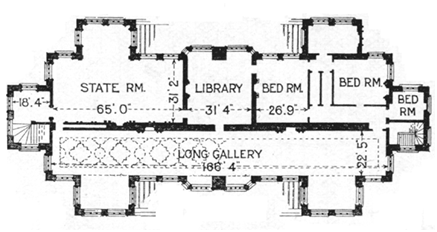

A lesson in Elizabethan Manor Design

So, I threw myself into researching Elizabethan manor design. Eventually, I uncovered the floor plans of other Elizabethan manor houses which had similar chimney arrangements. And there was the answer! What I hadn’t realized is that the front of the building (with all of the windows) contained a single, long gallery lined with the ranks of windows along its length. At Hardwick Hall, the house’s chimneys were aligned along the centerline of the house (to provide symmetry of the house), but such “long galleries” could also be heated by fireplaces located in the walls at the ends of the space. These long galleries were pure opulence: high back walls resplendent with tapestries and artwork opposing a rank of great windows gathering sunshine and looking out over fabulous Elizabethan gardens. Such spaces were perfect for entertaining and also served as a winter exercise space.

Analysis of the chimney flues available at the front of the Crown and Treaty’s second floor is perfectly consistent with a long gallery with fireplaces at the ends. Along the back wall of this gallery lie the doorways into the private rooms on that floor (each with their own fireplaces). At least some of these rooms have connecting doorways allowing them to be used as shared, adjoined spaces. The view from this long gallery must have been spectacular, looking out across the house’s large gardens and directly down High Street from a elevated vantage point. Perhaps it was more the point that the citizens of 1600s Uxbridge glancing up the street would find their view drawn to the distant face of this stylish mansion.

This was my first awakening that the building known as the Crown and Treaty wasn’t conceived as one of Uxbridge’s many inns–this house had been built to impress.

Armed with this new insight and an accounting of all of the fireplaces and windows, I created a set of speculative floor plans (see picture below). Of course, there is room for some variation in the placement of interior staircases and interior spaces on the western end of this building. But I believe the durable design themes of this structure are:

- the building itself was placed to dominate the view from downtown Uxbridge, and to make an impression on all the travelers of the High Road between London and Oxford.

- the main floor contained some receiving/parlor spaces and a handful of private rooms. It also included significant utility (storage and kitchen) spaces located towards the western end of the building (nearest the octagonal storage annex)

- the rooms on the second floor are slightly larger and better appointed than those on the main floor

- the long gallery on the second floor may have a significantly vaulted ceiling. I believe the rooms behind it do not.

- I suspect the center room on the second floor (with the square section projecting through the back wall) was used as a library or study (taking advantage of the extra light from those windows, and allowing its occupant to observe activities in the grounds and liveries which almost certainly existed behind the mansion)

- the attic space on the third floor is composed of larger spaces (and probably served as a bunkhouse-like living quarters for the live-in household staff)

- the stairway for the existing building is located toward the western end of the building and probably allows access to all 3 floors.

The Missing Part of the Original Treaty House

The front and rear of the existing structure appear to be original, so the rest of the original Treaty House must have adjoined one of its two existing ends. Although the end containing the octagonal storage structure has been most obviously modified, I found earlier drawings of the existing house in the 1800’s with large trees adjacent to that end of the house. Assuming that very large trees generally require the better part of a century to reach such maturity, it suggests that no structure existed on that end of the house as early as the middle 1700s. But what of the obvious (and amateurish) repairs on that end of the building? They (along with the octagonal storage annex) could well be the result of the result of structural repairs and modifications made to the building through the centuries.

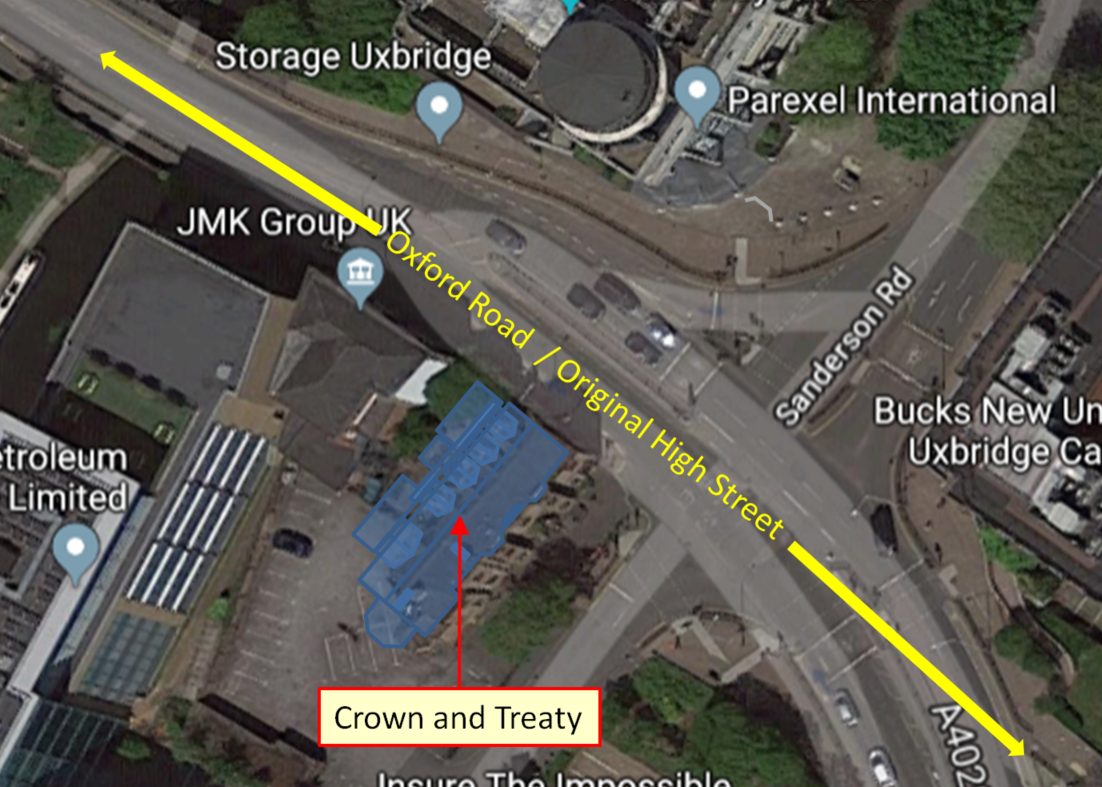

Thin accounts of the history of the house indicate that at some point, the center of the house was demolished to accommodate a rerouting of High Street. Looking at overhead imagery, it can be seen that the main street through town passes naturally past the easternmost end of the Crown and Treaty. So, it seems quite reasonable to consider that the narrow end of the building facing onto the current street was originally an interior wall which adjoined the center of the original house.

This is an interesting fact to consider. Observe the overhead image below and notice how naturally the Oxford Road leads into the path of the original High Street (Uxbridge’s historic main street). Since the ancient 5-arch bridge across the Colne River (just beyond the left of this image) and the historic High Road through town are aligned, it means the original Treaty House sat directly in the way of this road. The only way this seems possible is if the road had been redirected to flow around the grounds of the Treaty House when the house was originally built! As fantastic as this conclusion may sound, in the next article I will present evidence that this was precisely the state of affairs early in the house’s history.

Regarding the room where the treaty negotiations took place, accounts of the negotiations indicate this large room was located in the center of the house on the second floor. Given the density of fireplace flues on that end of the existing structure it seems clear there is no space in that part of the existing structure that could have accommodated the approximately 50 people (16 commissioners for each side plus support staff and attending VIPs) who would have been directly involved in the negotiations. Thus, it seems fairly certain the negotiation room was indeed in the adjacent part of the building (that no longer exists).

The “Presence Chamber” Goes for a Visit to New York City

Modern historical summaries of the Treaty House describe that the second floor rooms were lined with a sumptuous carved paneling (as seen in the photographs below). One of the surviving rooms lined with this paneling is billed as the “presence chamber”, where the king might have conducted business while staying there. Although there is no record that the king actually stayed at the Crown and Treaty (recall that during the Civil War the Crown and Treaty was behind enemy lines), it is entirely possible the house was designed to facilitate such an occasion.

Shockingly, in the 1920s, this beautiful historic paneling was apparently removed by the building’s owner and sold to an American businessman to adorn a new office in New York City’s Empire State Building. I cringed to think that someone could be so careless with such a historic feature, and more so when I read that it was an American who bought it. Thankfully, this story has a happy ending!

Apparently (30 years later), this elaborately carved paneling was removed from the Empire State Building and returned to Queen Elizabeth II as a coronation present. Although re-installed in the Crown and Treaty shortly thereafter, this paneling has been retained as the property of the Queen. This arrangement ensures this irreplaceable bit of Uxbridge’s heritage will never be so recklessly disposed of again. I can only imagine the fascinating restrictions regarding stewardship of this paneling that must be written into the agreements for anyone owning this building. In the end, I breathed a sigh of gratitude for the class the American owner exhibited in ensuring this minor treasure made its way back to Uxbridge where it belongs.

Of course, I couldn’t help wondering: could my model help me work out which of the existing upstairs rooms might be the “presence chamber”? I decided to give it a try.

Looking carefully at the photograph of this room (on the right, above), I noted a sharply defined shadow on the floor made by the visible leg of the side table on the right of the scene. That sort of shadow would be consistent with sunlight through an open door in an otherwise closed room (i.e. no other windows). Ray tracing of that shadow implies a doorway roughly in the center of the wall opposite the fireplace. The sharpness of this shadow also implies a brightly sunlit window situated a fair distance beyond that doorway. Noting the offset fireplace location and the rough dimensions of that end of the room, I checked my model to see if any of the second floor rooms seemed to uniquely match it. And one did!

The key was that I was independently able to locate a drawing of the room at the easternmost end of the second floor that confirmed my model’s estimate of that room’s fireplace placement. Assuming the other fireplace offsets are similarly correct, there is only one room on my model of the second floor that is consistent with the lighting, room dimension and fireplace offset seen in the presence chamber photograph. That room lies in front of the westernmost chimney set (as shown in the figure below). It would be interesting to find out someday how close this prediction was to being correct!

If this room really had been intended to be a presence chamber, it might explain what seems to be a large space adjacent to it. If this space had been a VIP accommodation (as I’ve assumed in my model), it would have provided a generous bedchamber with four windows and two fireplaces. In this configuration, it would have had its own stairwell access with a small room toward the front of the house where members of the king’s guard could have been quartered just outside his room. Of course, given the options of space and fireplace placement, this end of the house could easily have been in a different configuration to serve alternate design goals.

In my next article, I extend this research to provide an unprecedented reconstruction of the entire original Treaty House (including a detailed model of the negotiations room) as it existed during the 1645 peace negotiations!

—-—

Your comments and corrections are always appreciated. I admire great writing, but have little choice but to approach this task as one of grinding a workable edge onto a rough blade – with my thanks for your generosity of spirit and firm critique in the meantime!

–-Greg Sherwood