Although I have been able to do a great deal of research from America, some portion of existing historical material simply isn’t available online. In the end, there is no substitute for time spent a fluorescent-lit archive amid a sea of box-laden shelves–or comparing notes with members of the local historical community.

I was reminded of this truth while we were in Uxbridge recently. A member of the Uxbridge History Society shared a hand-drawn copy of a 1775 plan drawing from the Uxbridge Archives, and his own rare copy of a paper about the Treaty House by an accomplished modern historian. These two local documents provided a small trove of information that filled in a gaps in what I’ve been able to find–and one that disproved part of the model I’ve been developing of the original Treaty House structure. So, with thanks to Tony for sharing this information, I’ve been back at work on the Uxbridge Treaty House part of the Lane Project!

Analysis of the 1775 Survey Plan

Digging through materials related to the 1775 plan drawing at the Uxbridge Archives, I found that this document was a survey plan for the proposed straightening of the Oxford Road. This project, when completed, would irrevocably break up what remained of the original, proud property of “The Place”, two decades after the majority of the main house had been taken down.

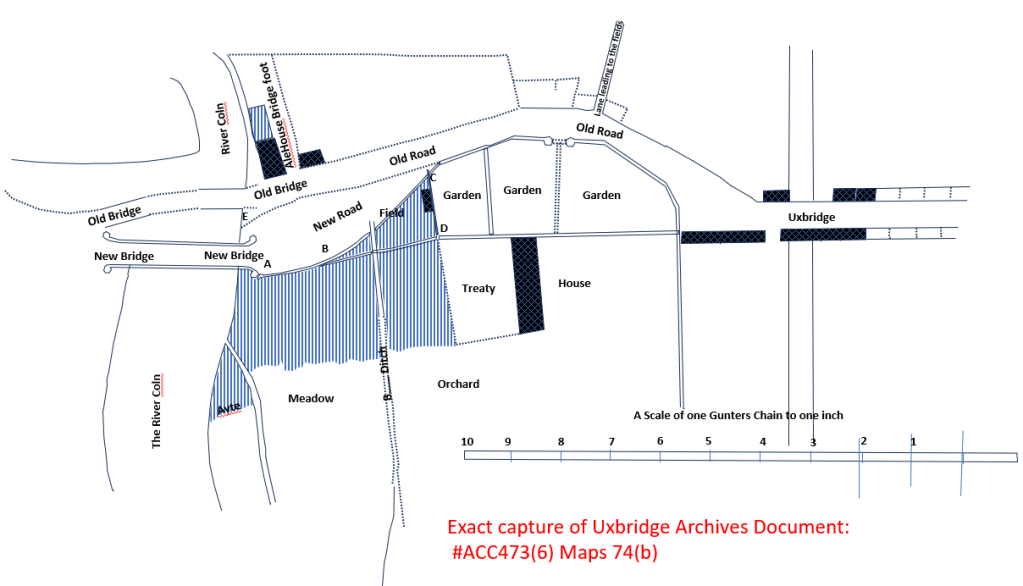

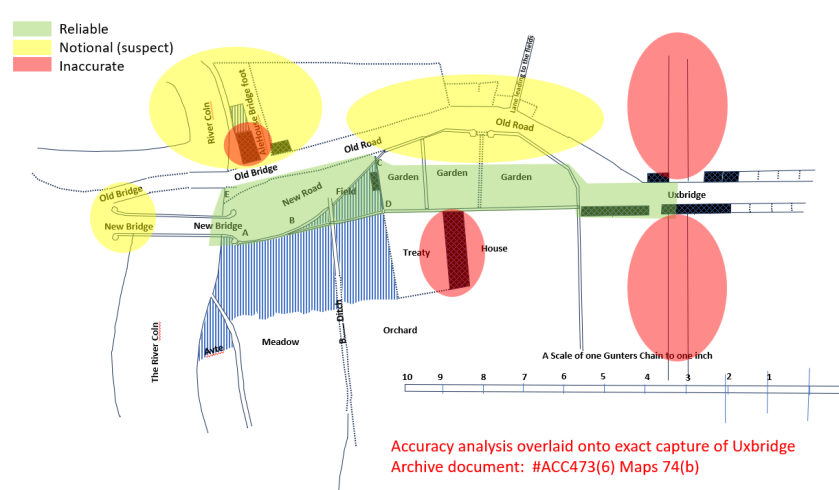

This is an extraordinary artifact, as it is not a sketch or artist’s impression of the scene. Rather, it is an engineering drawing that includes a surveyor’s scale, and was thus intended to be as accurate as it could reasonably have been made. The graphic below was taken directly from the document at the Uxbridge Archives. The information it contains is singular. Most diagrams I’ve been able to find of this area do not contain this level of detail, and are from after the new road was already in place.

There are several unique insights contained within this image. For instance, although I had read about an older “pack and prime” bridge that had been built in two segments over the Colne, I’d never seen an illustration of it. In the figure above, it is denoted as the “old” bridge. It also shows the footprints of the “Swan” alehouse and that of the remaining wing of the Treaty House (both of which still exist today).

Despite the fact that the scene depicted is of the grounds decades after the main house had been taken down (and the property was already being sold off in parcels), many vestiges of the original grounds are still evident. For instance, the image clearly depicts the twin octagonal gatehouse (“lodges”) that flanked the original entrance to the property. Especially useful to me is the shape of the “old” Oxford Road as it arcs around the property. Before this document, I haven’t seen anything definitive about the shape of the original property. The wealth of other details (walls, fences, cultivated fields, ditches and buildings) provide a unique and satisfying view of “the neighborhood” around the Treaty House property at that time.

There are several odd things about this image also. The Frays Stream (at right) is not a straight channel (as it is depicted), nor does it intersect the bridge and the town mill at the angle shown. Also, the gatehouses are placed at an odd geometry relative to the remaining Treaty House wing. as though the person drawing it didn’t realize that those structures were related. Prudent architectural sense would have placed the gatehouses parallel to, and centered upon, the original center span of the house. To get a better feel for what can be trusted in this image, I decided it was time to do some analysis!

What is a Gunter’s Chain?

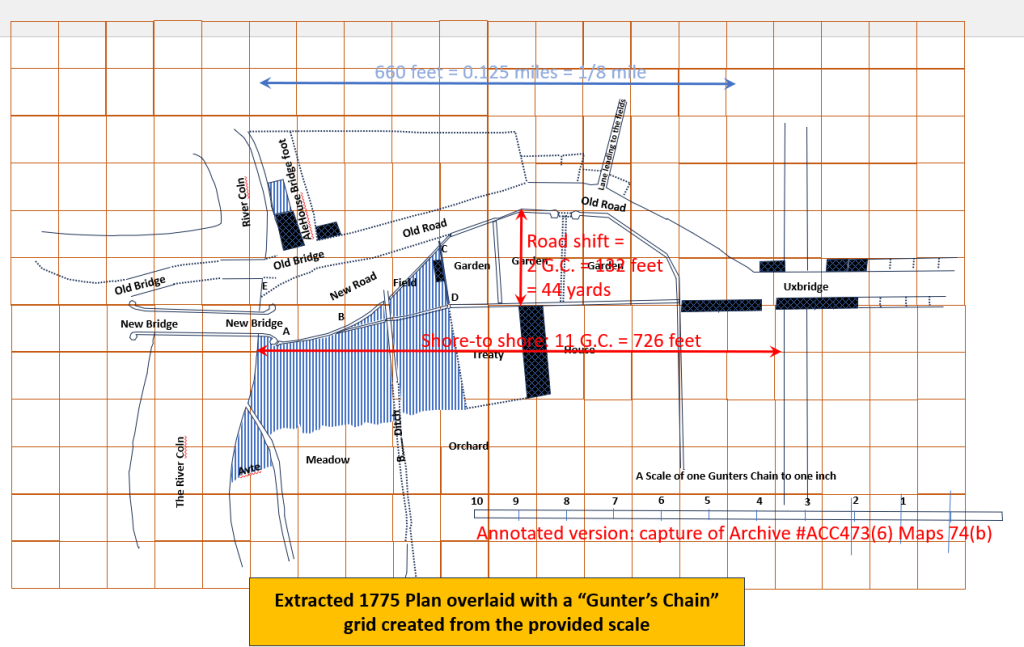

The text in the image refers to a “Gunter’s Chain” and provides a scale of 10 of these rulings in a line. A Gunter’s Chain was named after the English Clergyman and mathematician who introduced it in 1620, Edmund Gunter. It is a durable set of 100 links in a chain that is a total of 66 feet long, and is used exactly as we use a tape measure today–but for surveying.

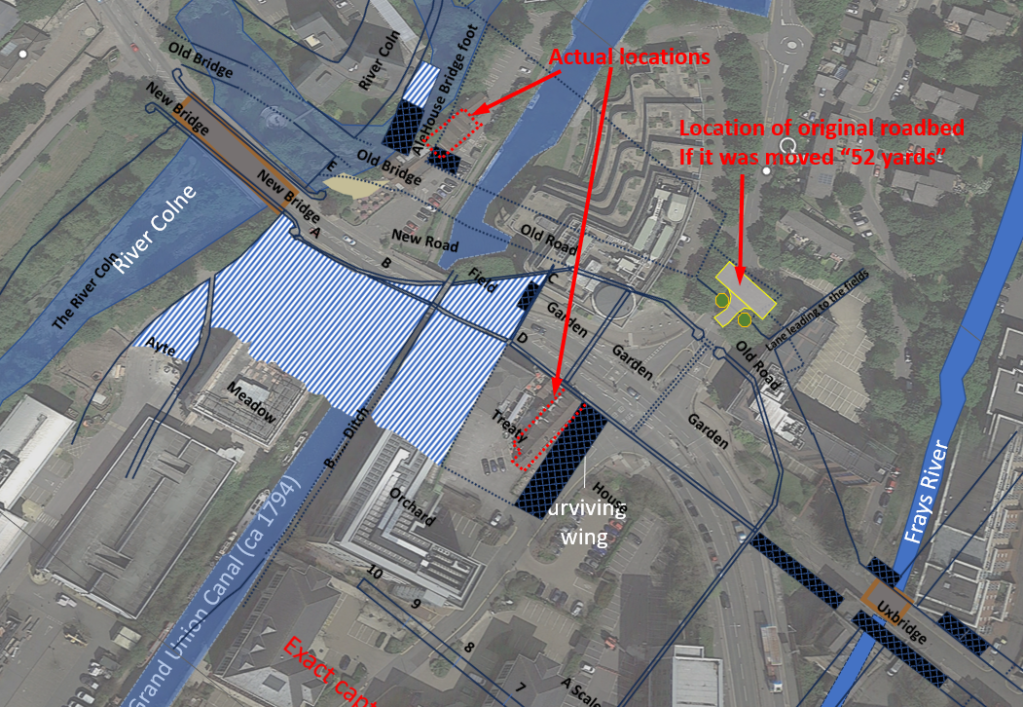

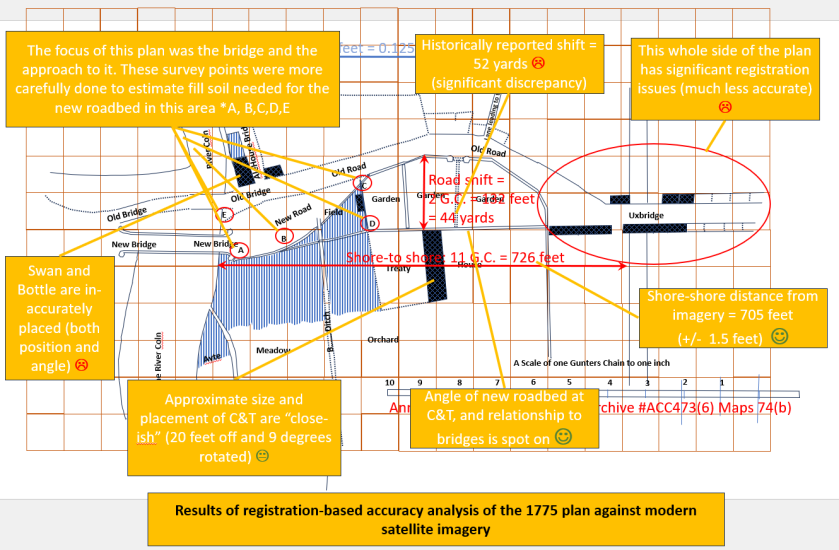

Having a surveyor’s scale in the image was simply too much for my inner nerd to pass up! First, leveraging the provided scale, I created a 2D “Gunter’s Chain” grid, which I laid over the survey image (see image above). Since each square in this grid represents 66 square feet, this grid can be used to make measurements on the image. Overlaying the 1775 survey drawing over modern satellite imagery of the same scene and using online distance measuring tools, I can use enduring elements in the scene to assess the accuracy of the original drawing.

First, I had to confirm that the accuracy of the online distance measurement tools themselves. If the measurement errors were larger than what I am trying to determine, then there is little point in going any further! Using the “measure distance” feature of Google Earth and repeating a specific measurement of a significant distance (approximately 1,000 feet apart in the image) achieved results with a “standard deviation” of about 1.2 feet. This is good, as this amount of error includes any intrinsic error in Google’s measurement tool and also my ability to reliably choose the exact same spots to measure each time. Next, I measured the roof peak of the Treaty house multiple times, and consistently got measurements of +/-6 inches compared with measurements of the building I made while recently in Uxbridge. Bottom line? These tools are more than accurate enough for this job!

I did not expect the survey map to be perfect. After all, it provides an overhead perspective drawn using only ground observations using 1600s technology. But I was pleasantly surprised how well the survey image laid onto key parts of this scene. In particular, the spatial relationship between the new roadbed and the bridgeheads at either end of it was nearly perfect. Also, the surveyed distance from one bridgehead to the other was 11 “chains” (726 feet). This matched satellite measurements (705 feet) of the same distance fairly well (given that I did not have clear visual targets for making this measurement).

But there were also some unexpected misalignments (see the analysis graphic above). The depicted footprints of the Treaty House and the Swan are both misplaced by at least 20 feet (in different directions), and both are somewhat rotated from their true orientations. Also, the twin gatehouses are depicted significantly closer to the new road bed than the “52 yards” the roadbed was (separately) recorded to have been moved.

The explanation for the variation in accuracy is that certain parts of the scene were carefully surveyed, while others seem to have been drawn in for completeness. If you look closely at the plan, you will notice a grouping of 5 points called out near the Colne bridgehead (labelled A, B, C, D and E). These are specific survey points that surround the planned roadbed where it approaches the new bridgehead. In fact, the text on the plan calls out how much fill dirt would be needed to fill in this part of the road. It also makes sense that the width of the island was more accurately measured, as the length of this section of new road would have been a key metric for the project.

But those areas which lay outside the new roadbed were not directly relevant to building the new road. These details were made for completeness of the scene, and it appears were less accurately captured by the engineer that created this plan. The next graphic of the scene summarizes which regions of this diagram I was able to validate as accurate, and others that are either suspect, or were revealed to be inaccurate.

Dr. Richard Spence’s Article on “The Place”

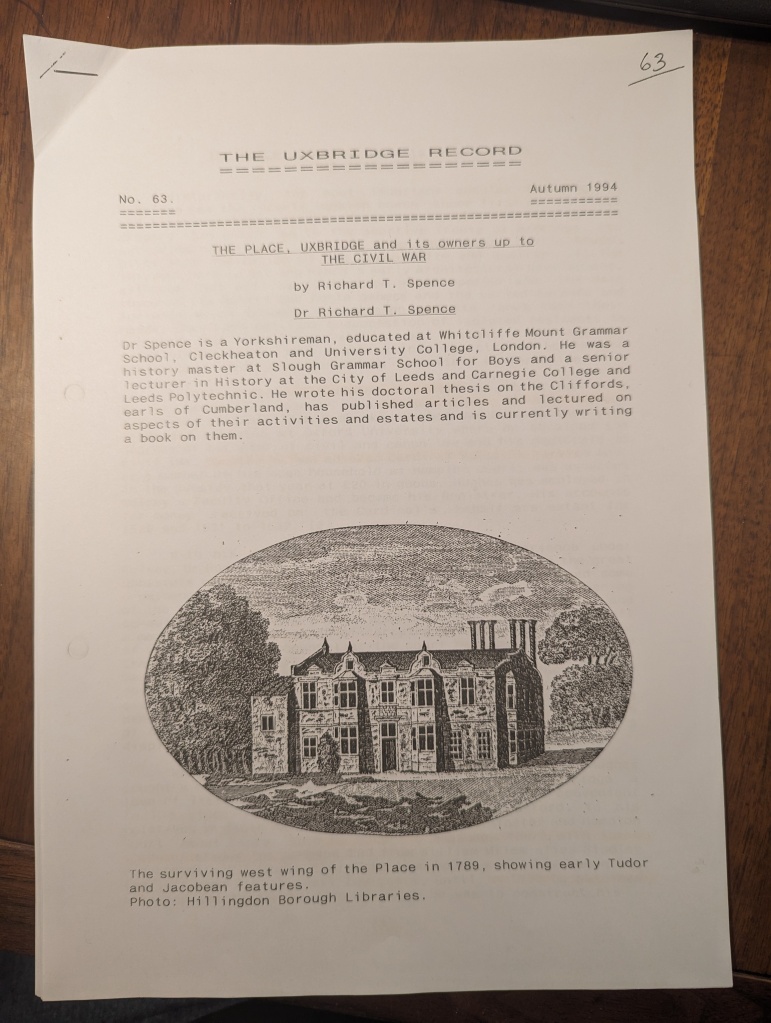

The second important artifact I obtained in Uxbridge was a paper published in the Autumn 1994 edition of The Uxbridge Record (by the Uxbridge History Society). This is an excellent paper about the early history of “The Place” (as the Treaty House property was originally known) and those who built and later owned it.

I was surprised to learn that the author, Dr. Spence, was not a local resident–he was from Leeds, far to the north. Like myself, Dr. Spence’s attention seems to have been drawn to Uxbridge by a thread of his primary research focus. After losing his role as a Senior Lecturer at Leeds and Carnegie College during a educational consolidation at age 54, Dr. Spence retired early and threw himself into the topic of his original PhD thesis: the history of the Clifford family (Earls of Cumberland). He authored several books regarding the Cliffords and several places related to the family.

The thread that seems to have brought Dr. Spence to the Treaty House was the granddaughter of Dr John Hughes, who originally built “The Place” in ca 1535. In her adulthood, this daughter (Grissell) married a man named Francis Clifford. The newly married couple first lived at “The Place” while Francis was constructing a bold new home amidst the rest of the Clifford family in Londonborough. Some years later, Francis succeeded his brother and became the next Earl of Cumberland. Lady Grissell (daughter of Uxbridge and raised at “The Place”) was now a countess.

Apparently pursuing this marital link between the Cliffords and Uxbridge, Dr. Spence became interested in the Treaty House and wrote his excellent paper on it in 1994. This paper was a privilege to read. I would have loved to have met Dr. Spence, but he died in 1999–5 years after making this unique contribution to Uxbridge history. The Guardian news site has a wonderful online obituary that describes him (Richard Turfitt Spence) as a warm, gentle and witty historian and an avid club cricketer. I was able to find 6 books he published, most available on Amazon. Unfortunately, I was unable to find a photograph of him, or I would have included it. So, with a salute for excellent, singular work and the significant help it has provided me–many thanks, Dr. Spence, and rest well.

For my work, there were several worthwhile discoveries in the Spence paper. First, while Lady Grissell and her husband Frances Clifford were living at The Place, arrangements were made to receive a visit there by Queen Elizabeth I (and her retinue) in October 1592. His description of the effort undertaken was fascinating, although Dr. Spence tells it is not clear the visit actually happened. Recall that this royal visit would have taken place only a few years after the Elizabeth I had so capably led the defense of England from the invading armada of King Phillip II of Spain in 1588. For Americans who aren’t familiar with this, watch the academy award-winning movie, Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007)–it was Elizabeth I’s “Churchill” moment. She was at the height of her power, and her reign was an era of prosperity and relative stability compared with the chaos and religious whip-sawing of the country by King Henry VIII and his immediate successors. I suspect if this royal visit had actually taken place, it would have been an important local event that would have become part of the fabric of the property. The additional notoriety might even have saved the estate from its ultimate fate…

A few years after Francis Clifford and Lady Grissell had moved to their new mansion at the Clifford family seat in Londonborough, the Uxbridge property was sold to Sir John Bennett in 1613. Apparently, the new Earl Francis Clifford had inherited significant debt along with his new title, and the sale of “The Place” was necessary to help resolve them.

Sir John Bennett was already a significant landholder in the area who desired a convenient and enviable estate commensurate with his status. Sir John undertook the first great renovation and improvement of the property in 1623. As part of this costly expansion, the attic areas of both wings were built out to provide additional accommodations for his 10 children, 40 grandchildren, servants and guests.

Dr. Spence tells that the original chimney structures contained a single flue in each turret. But as hearths were added to heat the new rooms in the attic spaces, additional flues for them were carefully fitted into the center turrets of the chimney structures. Additionally, Dr. Spence notes there may have been a revamping of an original “great hall” in the center span of the building. This update (which likely also included the fitting of the famous carved paneling) would have created the elegant spaces utilized during the treaty negotiations in 1645. With the completion of this work, the significantly upgraded property took on a new name, becoming known long after Sir John’s death as the “Bennett House”.

There was one important detail in the paper I need to disagree with. Dr. Spence about. He speculates that the “good stairs” described to be at both ends of the center span’s main chamber were contained in angle turrets (as exists at the far end of the building today). However, that octagonal structure is not present in depictions of the building from the post demolition period of the latter 1700s. Although quite functional (having used them), it’s difficult to imagine anyone remarking upon them as “good stairs”. But most telling is the presence of filled-in windows in the end wall of the building which are unaligned with floors. These windows are clear evidence that an elegant stairwell was originally located within the end of the existing wing.

Reviewing the brickwork that connects the octagonal structure to the far end of the building (and various images of the building over time), my own suspicion is that it was added sometime during the middle 1800s when the Treaty House (and the large building appended to its backside) served as an Inn.

Finally, I was amused to read Dr. Spence’s mention of a “hearth tax” of 20 hearths on the property in 1674. This caused me to smile because the three chimney structures of the existing wing alone contain 12 flues. If the opposite wing was symmetrical, there would have been 24 flues before even considering those needed to heat the large center section of the building! My current model estimates there were an additional 2 flues at each end of the center span of the house and at least 2 full sets of chimney stacks along its back wall. This would have resulted in a total of around 34 hearths in the house at the time this tax was assessed. Apparently, tax dodging is a very old game indeed!

Layout of the Original Treaty House

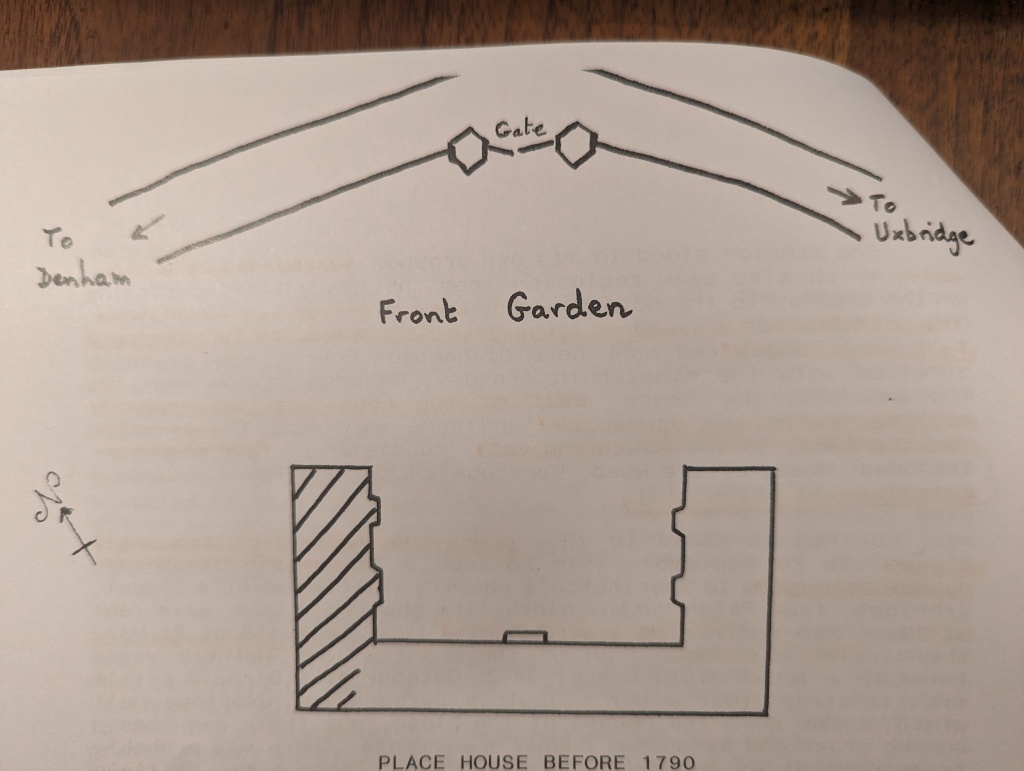

Dr Spence’s paper includes a sketch of what the original structure might have looked like. Apparently, Dr Spence shared my suspicion that the spatial relationship of the remaining wing and the gatehouses depicted in the 1775 survey plan was not fully accurate. As Dr. Spence has illustrated, it is far more likely the twin gatehouses would have been centered on the house and arranged parallel to the face of the center span.

In my next article, I will share the the resolution of some nagging incongruities with the simple layout depicted above. There is more to know about how the wings actually attached to the center span. The clues lie in the tortured walls at the far end of the remaining structure…

For the last few years, Mary and I have been discussing the possibility of an extended visit to the UK that would allow me to do some much needed in-person research for this project. With the wind-down of the pandemic and the passing of a much loved, furry member of our family last year, we have decided it’s time.

We are both excited and nervous, of course. Its already hard to think about being away from our friends and family for an extended period, but this is something we don’t want to look back on later and regret not doing when we could still do it well. Having made new friends in Uxbridge, we are very grateful we will have a community to make our own for awhile. It will be wonderful to do simple things like making meals together!

Of course, we plan on making the most of the opportunity for adventure, and are bringing our road bikes and hiking poles. We are looking forward to exploring a great deal of England, Scotland and Ireland (and our most yearned-for places in Europe) in our down time!

For now, we still have quite a few arrangements to make, including finding a fill-in drummer for my band. Regarding my research, I am filling out my list of topics I haven’t been able to run to ground from America. I will also have to decide which books I will really need to have with me. But by this fall, I hope to be putting in some quality time in the archives of London, Oxford, Northampton and Somerset. And making time to meet with some acquaintances we’d enjoy seeing again–especially without having to rush the visit this time!