Anyone who has ever parked at the Crown and Treaty in Uxbridge has noticed the collection of oddities that is the far end of the Treaty House. Contrasting with the lovely main face of the existing building and the towering and artful chimney structures on its backside, the far end feels architecturally discordant, improvised and beat up. Things just don’t seem to make sense on that end of the building. And the closer you look, the stranger it gets….

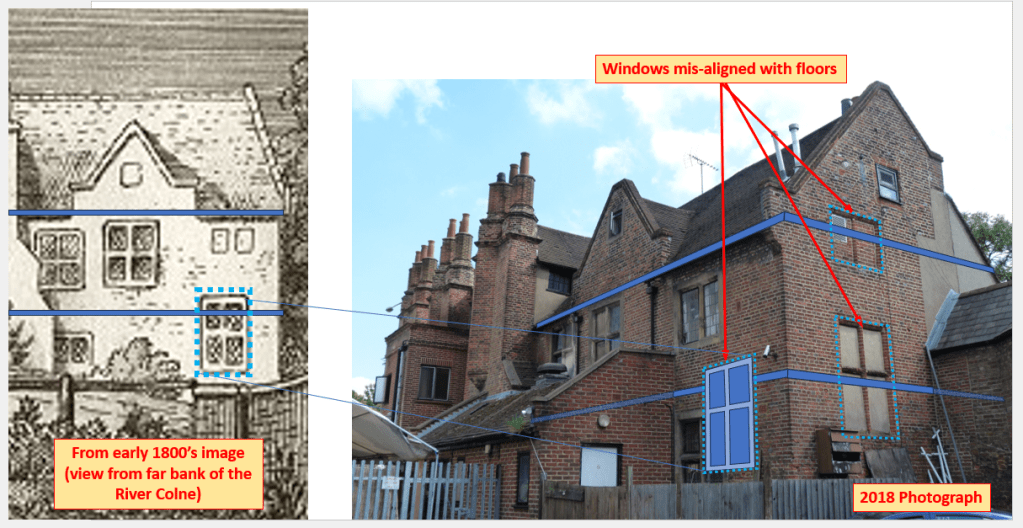

Part of my struggle with this end of the building is that its so difficult to unravel. Nearly 500 years of maintenance has left the mark of many obvious repairs, including a large section of concrete shoring on the end face of the building. There are multiple swathes of mismatched brick, and brickwork patterns that don’t match those of the other end of the building. There are bricked up windows, concreted windows, glaring repaired cracks and a jagged, abruptly-ended facade. There are windows clearly out of alignment with those on the rest of the building. It seems a mess. But why? How did it come to be this way? And most importantly to me: Which parts of this end of the building date back to the time of the 1645 treaty negotiations?

The Octagonal Turret

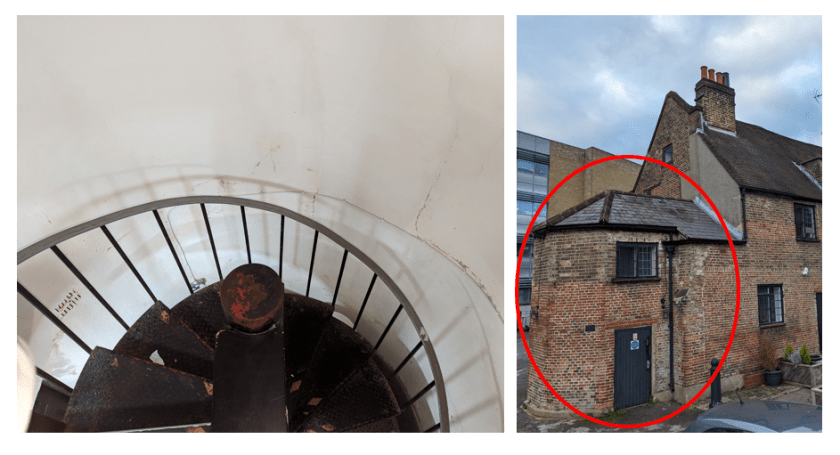

Protruding from the far end of the Treaty House is an octagonal “turret” structure. In my recent visit, I learned that this structure contains an iron spiral staircase that doesn’t quite make it all the way to the second floor (considering the ground level to be the first). At the top of these stairs, you cross into the main building at an intermediate landing, where you can then either jog to the right and ascend a few more stairs to reach the second floor, or proceed up a next, narrow set of stairs that carry you up to the rooms of the attic level.

In his excellent paper on the Treaty House (see my last article), the historian Dr. Richard Spence speculates that this “angle turret” (and its twin at the end of the long-demolished parallel wing) may have held the “good stairs” remarked upon in accounts of the 1645 treaty negotiations. This was not an important point in Dr. Spence’s paper, but I need to address it, as I have come to an important, different conclusion.

Reviewing the available historic imagery, it can be shown that this octagonal structure did not appear until likely a century after the majority of the original Treaty House was demolished in the 1750’s (of course, we are working all this out because there is no surviving imagery of the original house and grounds). For example, it is not present in the 1770’s “dilapidated” image of the Treaty House (see the left side of the graphic above). I believe this improvised structure was added no earlier than the middle 1800’s, perhaps at the same time a large building containing additional rooms was appended to the back side (the chimney wall) of the existing building.

The “Good Stairs”

Accounts of the 1645 treaty negotiations describe a large, well appointed main chamber in the center section of the house. This spacious chamber was on the second floor, and was remarked as having been accessed by “good stairs” at either end. In this context, “good” stairs meant they were roomy, comfortable and stylish.

Despite the extensive rework in this end of the building and that the probability that these “good stairs” have not existed for centuries, there are still important clues about them. In particular, the western end wall of the Treaty House contains two substantial, but oddly placed windows. Both are blocked off.

The lower of these two windows is among the largest windows in the building. If you examine the brickwork around it (see the photo below), you will see the same fine materials and nearly the same level of craftmanship as in the windows on the building’s primary face. Although this wall has endured many adjustments and repairs over the centuries, this window (and the brickwork patterns around it) testify that the wall itself is original.

The artful brickwork in the transoms of this closed off window on the back wall match those of the windows in the building’s primary face. Both the materials and workmanship strongly indicate this window was original.

But these two were not the only stairwell windows. Looking at the early 1800’s image of the “Crown Inn” (as it was known at that time), you will notice the current windows at this end of the building’s back wall do not appear in that historic drawing. Instead, the drawing shows yet another grand but oddly placed window, and a pair of smaller “sunlight” windows just under the eave of the roof above it.

During daylight, all of these windows would have provided illumination of the stairs. They also would have provided generous views of the grounds to those using the stairs to pass between floors. The next figure is my initial cut at a possible elegant stair arrangement that aligns with the placement of these windows. I’m not yet convinced this plan is correct, but its good enough for now. To help with visualization of the original house design, I have “photoshopped” the rear wall of the building to reflect how it would have looked at the time of the early 1800s image of the “Crown Inn”.

I assert that the original stairwell survived until at least the early 1800’s (and was probably removed in the middle 1800s when the building was expanded). If you look closely at the early 1800’s drawing from the banks of the River Colne, you will see there are no appended structures on the chimney side of the building, and no sign of the octagonal stair turret later appended at its end. This would have left an internal staircase as the only way to reach the second floor.

The presence of the second, smaller unaligned window higher up on the end wall indicates some continuance of the stairway to reach the rooms Sir John Bennet added to the attic spaces in 1623.

There is also a small set of stairs just above the modern main entrance by which the attic spaces can also be reached from the second floor. This cramped stairway has the feel of a fire escape or staff access. The stairs themselves are clearly modern, but some version of them were likely either original, or installed when the attic spaces were built out in 1623.

The Puzzle of How the Center Span Intersected the Surviving Wing

The next mystery is most significant I have wrestled with since we returned from Uxbridge. How did the structure of the center span of the original building intersect with the surviving wing? The image above appears in Dr. Spence’s excellent 1994 paper on the early history of the Treaty House. The building arrangement he has drawn assumes what I am calling a “full corner join” of the original center span with the surviving wing (which is shown hashed, on the left in his drawing above).

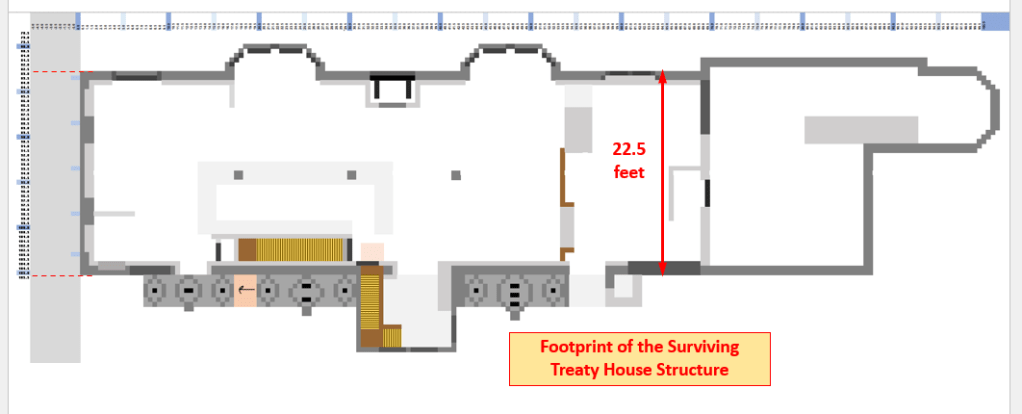

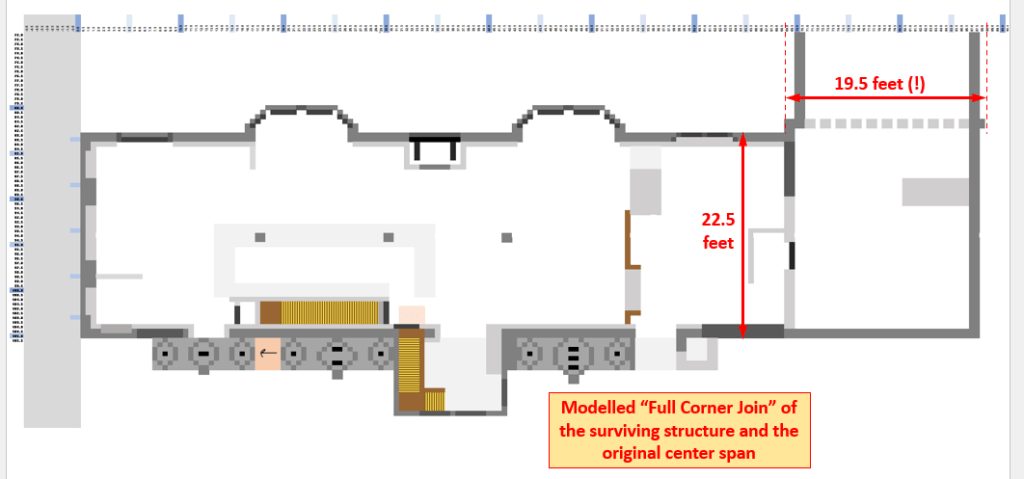

I started from this assumption as well, but ran into an important issue when I tried to model it. Lets start with the footprint of the existing building (next figure). To avoid confusion, ignore the “octagonal” structure projecting from the right end of this figure (as we discussed earlier, this structure was not part of the original building).

There are two critical considerations. First, judging by the age of the bricks, the brickwork patterns and the existence of original (albeit closed off) windows, the end wall (towards the right in the graphic above) appears to be original. Second, there are fairly clear structural oddities in face of that end of the surviving wing. This must have been where the original building connected, but how, exactly?

A dimensioned model of the “full corner join” (as appears in Dr. Spence’s drawing) between the surviving wing and the original center span is accomplished by carrying the surviving end wall along as the rear wall of the original center span (as illustrated in the next figure). The problem I just couldn’t get comfortable with is that this would have made the center span significantly thinner than the wings.

I double checked my measurements and geometries, and found no flaw in them. For awhile, I wondered if the end wall might have been moved or rebuilt. But this would have involved a great deal of effort and resulted in less interior space in the building. Also, moving this wall would have implied moving the staircase behind it as well. Taken together, these make the possibility that the wall had been moved very unlikely. Next, I considered whether the front face of the original center span might have intersected the existing building closer to the adjacent bay columns. However, this would have landed the wall squarely in the middle of an apparently original window. None of these possibilities seems reasonable, including the idea that the center span wasn’t built to at least the same roominess as the wings.

I was describing my exasperation to Mary about the strange mix of clues at this end of the building when the light finally came on… I remember grumbling about how the large patch of concrete shoring made an ugly scar on an otherwise lovely building when the analogy of a scar rang a bell in my mind. I may even have stopped speaking in mid-sentence.

What if a scar was exactly what that concrete shoring was? Not a hasty patch job to stabilize a weakened wall (as I had assumed), but the point of amputation of some part of the original structure? Was it possible the center span and the wings were were originally joined in a more complex, partially overlapped intersection? I had to admit it would have made the overall structure stronger…

And there it was. In the figure above, you can see the vestiges of where the center section of the house connected to the surviving structure. Looking at it now, I believe this odd, slightly protruding section of wall was once the last structural “rib” of the original center span. Rather than remove it, the bricklayers left it in place and bricked in the span between the rib structure to fashion a new outer wall for this part of the remaining wing.

The figure above illustrates what the footprint of this “offset join” of these parts of the building would have looked like. In this model, the outside faces of the center span’s walls would have been 23.5 feet apart–1 foot more than in the wings. Finally, I had a join concept that aligned with both the evidence and basic architectural sense!

Subtle Buttresses in the Structure

Although unconventional, this plan could explain a number of things. Considering this odd protruding wall section as a “filled in” vestigial rib from the end of the now absent center span helped me see it differently. And in the bargain may have resolved another minor mystery.

If you look at it closely at pictures of this protruding section of the existing building, you notice it is wider at the first floor than at the second. It didn’t make sense to me that this had been the shape of the center span wall. I didn’t know what to make of the odd protruding shape in it–that seems to be original. If this were the normal thinning of the wall structure at the succesively higher floors, the outer wall would have been left flat, leaving a ledge on the inside where it could support the joists of the next floor. This would have left the the outside wall flat, matching the adjacent, attractive face of the surviving wing.

I now believe the wall of the center span was vertically flat, with the lower portion of this structural “rib” protruding from it at this location only.

We’ve all seen something like this before, albeit on a much larger scale–in the construction of most historic churches in England. To illustrate what I mean, the image above is of the home church of the Templar Knights in Middle Temple, London.

When a large spanning roof (one without posts to hold it up in the middle) settles, it pushes outwards on the tops of the walls, weakening them. Buttresses brace the wall from its outside to prevent this spreading from taking place. Buttresses are a important part of why these ancient buildings have lasted so long.

In the case of the Treaty House, the span is moderate, and the large chimney stacks along the outside of the building and the bay columns along its inner face would provide a fair amount of reinforcement to the walls. It may be that the builder wanted this small buttress as a bit of extra reinforcement where these walls intersected.

Modelling what the offset join would have looked like

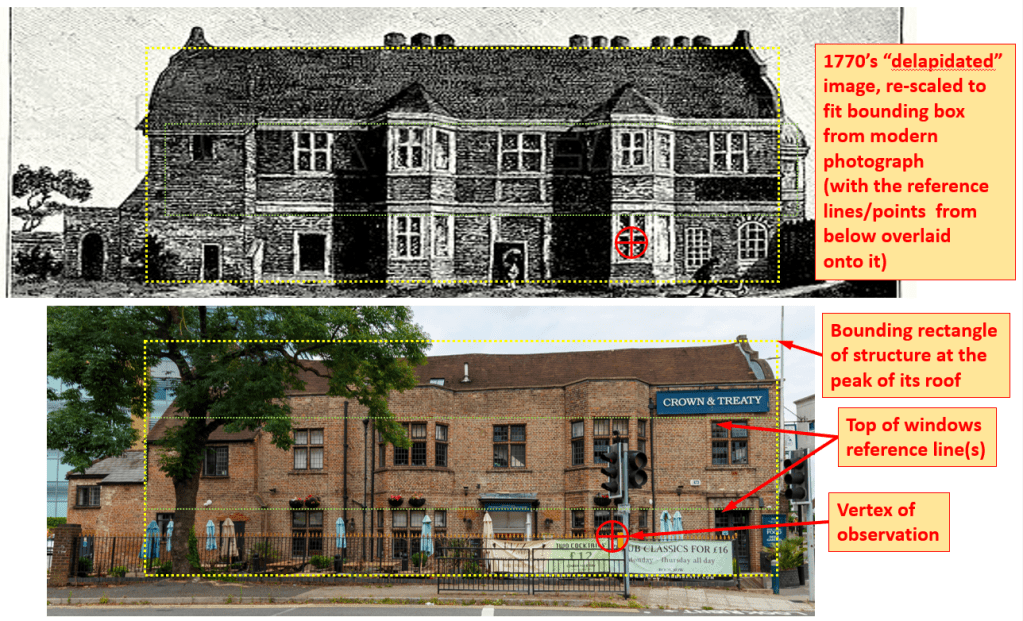

In the next set of images, I have scaled the “dilapidated” image of the Treaty House in the 1770’s so that it lies as closely as possible within a bounding box made from a modern photograph taken from nearly the same point of observation.

Comparing these images side by side reveals several notable things:

- First, at some point, the walls above the second floor of this wing were extended upwards by several feet. This taller wall face makes the roof seem smaller than it was originally. This extension of the upper walls likely took place during the early 1800s remodel.

- The 1770’s image of the Treaty House shows no other visible chimney flues except those of the the primary chimney stacks. It is not clear how this end of the building would have been heated, but suggests that the spaces at the left end of this structure were large enough that the existing fireplaces along the back wall were deemed adequate when the rest of the building was taken down. In the modern image, two new chimneys are present the left end of the modern roof. These were likely added in the early 1800’s remodel, as they appear in images made soon after that remodel was completed.

- Although the residual structure that lies beyond the left end is depicted to be different than what is present today, it includes the same first floor portion of where the original back wall intersected the surviving structure.

- The roofline in the modern photograph appears to increasingly sag as you move to the left. Although I have observed some localized sagging here and there on the roof, this general apparent sloping is mostly due to the image not being level and a bit of linear perspective shrinkage when looking at parts of the structure that are further away from the observer.

- The 1770’s image shows that the curved gable was originally present on both ends of the surviving wing. At some point, the curved gable was removed from the far end of the building (furthest from Oxford Road) and replaced with a simpler, non-curved top. This was probably done at some point to salvage materials needed to repair the Oxford Road-facing gable. This curved gable is executed in curved stone, which would have been difficult to replace if some of it had been damaged.

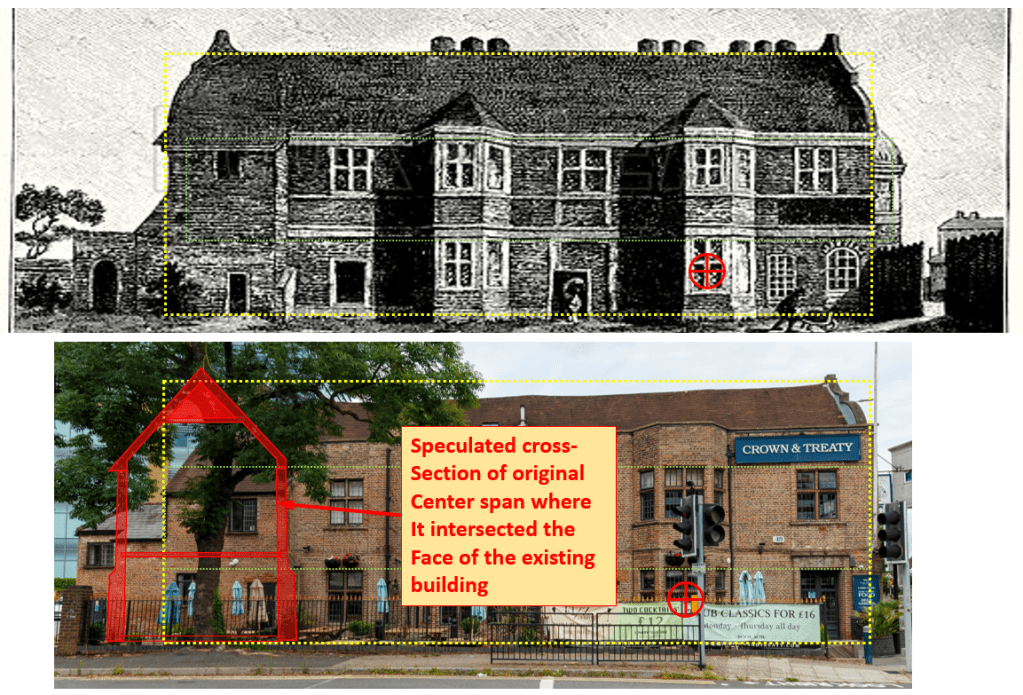

In the figure above, I have highlighted the likely shape of the original center span at the plane it intersected the surviving wing. There are a few things to notice about this cross-section. First, there is no attic level in the center span of the building–the second floor would have had a high, vaulted ceiling to form the great chamber there. You will also notice that the walls are significantly thicker on the first floor than on the second. This trend almost certainly continued underground, with the walls expanding even further at the foundation level (see the next figure). This was a common construction technique to spread the building’s weight over a larger area to keep the building from settling into the ground.

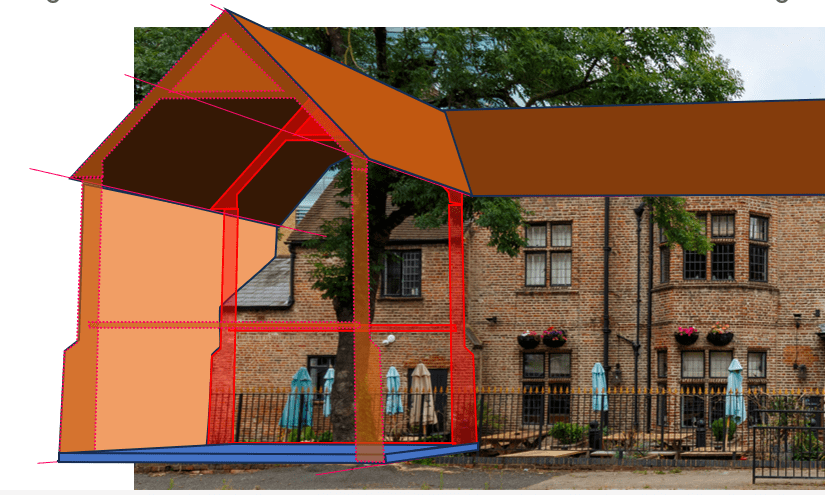

The next figure takes the modelling further, showing a roof plan and a projection of the center span away from and onto the surviving wing.

I am quite interested in any feedback from the community on this most recent work, and particularly any examples of relevant historical architecture from this period. I am considering using my next article to pose some specific questions for input from the community following this project. I am intrigued by the idea of seeing what a bit of historic architectural “crowdsourcing” might turn up regarding a set of points I could use some help with!

Most importantly, I am hoping that when the artist supporting this project (Rhonda, who many of you met while we were in Uxbridge recently) gets the real 3D computer model of the structure in place, we will be able to look more closely at how the plane of the center span’s roof might have reasonably intersected the end gable. I am hopeful that will finally explain the shape of the concrete “scar” on the end wall of the existing building.

Life is interesting. And recently, it got far more so. Its not uncommon to find an earnest discussion of how the problems we face should be solved. But I was offered something very few people ever are: an opportunity to put my thoughts on what my country needs to the test.

I had the honor of being asked if I would be willing to be the candidate of the Forward Party to run for a seat representing Colorado in the US House of Representatives.

Each time I have have travelled to the UK, I have been asked what to make of the chaos and extremism that has manifested in American politics. Its an understandable question (and one I have thought much about). I think there may be some comfort in my answer. You see, we Americans do make progress as a society. Within the short span of my own lifetime, we have gone from a racially segregated society (i.e. before the Civil Rights Act of 1964) to white Americans electing a black man for president–twice.*

The understandable consternation is that on the path of progress, our society seems to find its way by lurching left and right like a drunken sailor. We somehow need to discover the consequences of bad ideas (and policies) by crashing into them. Then, we recoil (newly educated and muttering), before veering off in another direction. In the long run it seems to work, but its not pretty.

So my answer to my overseas friends has been: think of American politics as a pendulum. Its average position over time is its reasonable center. But you just have to grit your teeth while we take various reasonable underlying intentions too far. It will eventually swing back. I expect the current bewildering political scene to resolve itself in about 5 years.

In the current, embarrassing lurch, both of our major political parties have been co-opted by the extremists in their ranks. In an attempt to appease the torch and pitchfork waving gangs within their ranks, both parties seem determined to put up presidential candidates that would have little chance against even a modestly solid opponent. Each party is counting on disgust with the other party’s candidate to motivate their moderates to hold their nose and vote for their own, “less bad” candidate. And that’s where a third party in America may just have its moment…

There are currently two notable political movements trying to organize the moderate middle of America: the Forward Party and No Labels. Unlike other issue-driven parties (like the Green Party), these two are founded on the same basic premise–that it’s time for the moderate middle of American society to find its political voice. I support them both.

Apparently, I had been noticed in online Forward Party discussions I have participated in. It turns out that someone I respect, (and had gotten to know) was part of the Colorado leadership of the party. He also knew that I live in District 4.

It was a shock when he contacted me with a bombshell of a question: would I consider running for the seat being vacated by Congressman Ken Buck representing Colorado’s 4th district?

This seat is actually in the national spotlight, as Ken Buck is retiring early. Although he planned to retire at the end of his term, it is believed he chose to do so early to disrupt the survival plans of an embarrassing (and extremist) current representative of Colorado who was on track to lose her current seat in this fall’s general election. To avoid this, she had recently switched districts to run for the seat Ken Buck was planning to vacate. But with his early retirement, there will now be a special election in June, placing her in an awkward situation. If I ever find myself in the same room as Ken Buck, I intend to offer to buy him one of Colorado’s excellent craft beers.

For my part, it was an honor to be asked. And it was an opportunity that will not come again. In the vetting meeting, I was introduced to a spectrum of the people who are among the leadership of the party, from both the state and national level. It was a very candid conversation, and one that left an admiring impression on me. These are good people. They are talented and dedicated hard workers who who care deeply about the country. They struck me as the very embodiment of the ethos of “country over party”, and they expected the same of me. They cared deeply about ending the extremist antics that dominate our politics and threaten both our country and the stability of the larger world. They wanted to ensure that I shared the values of the party, and that I believed in the primacy of the rule of law. So it was a very comfortable conversation–I could not be more aligned with the need for a party committed to the principles this country was founded on (even if we haven’t always lived up to them).

It would have been a long-shot candidacy, but I am not averse to fighting a good fight. But in the end, I couldn’t get past the fact that politics at that level is a bare-knuckle, dirty fighting brawl. In this sphere, your ideas will never see the light of day if you don’t have the resources (political connections, personal wealth and lawyers) to win the disinformation wars against special interests and political opponents variously threatened by the solutions you are advancing. And there are clearly those who would have a hard time getting their heads around some of the solutions I would have fought for…

For example, I feel our immigration problem is only complex because we have corrupted ourselves. America is a country of immigrants. It is one of our core strengths. We should open the gates wide to facilitate the legal and timely inflow of people who want to work, share our values, and are willing to live within our laws. We should also offer a requirements-driven path to eventual citizenship for those who want it. But there’s a sticky part: we need to start enforcing our existing laws–not by cracking down on illegal immigrants, but by prosecuting those Americans who exploit those migrants. Eliminate the demand for unlawful labor. If you’re going to win that one, you need to bring more than a knife, because that will be a political gunfight.

So, I was assessed as an engaging, effective speaker and a natural advocate for the Forward Party’s values. The fact that I am not a career politician is an advantage. Having spent 15 years volunteering at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science established a clear background of service. My personal background in agriculture (born to a ranching family and raised in Wyoming), energy (a year in the oilfield as a wireline technician) and technology (I have 5 patents and was most recently a Product Owner for Cybersecurity and Enterprise Architecture at a satellite imaging company) would also have served me well.

In the end, I had gotten unanimous support to be nominated as the Forward Party candidate. They recognized I was a political novice, and were ready to line up resources to help me round out my knowledge of key issues, fundraise and create a plan for media engagement. But a thought I had posed in the vetting meeting rang in my ears for the weekend I had to think about it: “If I could cure cancer it would be one thing–I’m not afraid of a fight. But I have to think hard about putting my family through a wood chipper if I don’t have the resources to accomplish something worthwhile.” We have to make choices in this life, and ego alone is a poor reason to derail the meaningful life Mary and I have built together.

So, with clarity and some mixed emotions, I ultimately chose to thank them for the honor of their consideration and to decline the offer. Although I think there will always be some part of me that will wonder, “What if…”, I believe my path is to serve in other ways. Nothing would make me happier than to help the candidate they ultimately find carry their message to the voters and win that seat in congress.

* Unsurprisingly, more than 90% of black voters voted for Obama in the 2008 elections. Far less known is that it was the white vote that put him in office–there were more than 2 white votes cast for Obama for every black vote he received.