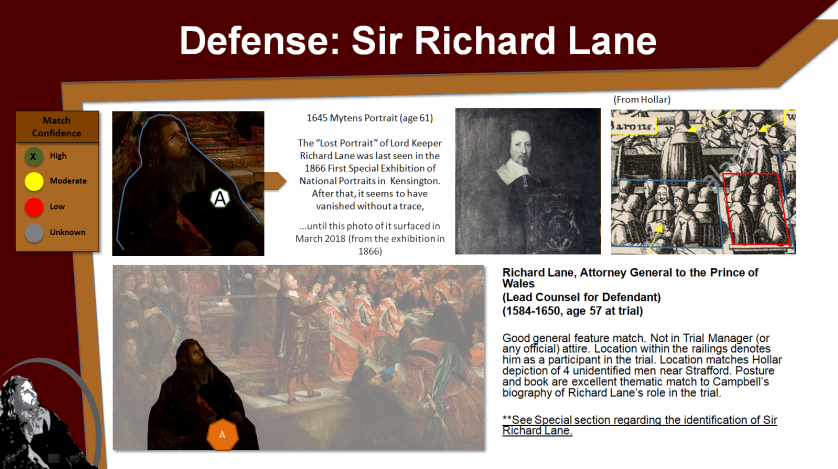

Welcome to the final (and best) chapter of the “Trial of Strafford” analysis! We have reached the core of this historic drama–the Parliament’s 1641 prosecution team versus Lord Strafford’s muzzled and thinly tolerated counsel for the defense. We have come to the reason I became involved in the story of this painting in the first place: the possibility that Thomas Woolnoth (the artist who created this historic 1844 painting): 1) knew about Richard Lane’s role in the trial, 2) had access to Richard Lane’s (now lost) 1645 portrait, and 3) deliberately included him in the cast of historical portraitures depicted within this dramatic painting.

Of course, it is the modern drama around this painting that really has my attention. Who could have predicted that I’d find strong cause to believe that Richard Lane was not only included in this remarkable painting, but that his uphill battle against the powerful and determined forces within parliament may have been a key subtext of it?

Finalizing my analysis two months before I departed to present it at Westminster, I had resigned myself to the fact that my analysis had a critical weakness: there was no known image of Lord Keeper Richard Lane to compare to the image in the Woolnoth painting. Richard Lane’s only known portrait had disappeared after an exhibition in 1866. Since early photography was in use at this time, I hoped that if the portrait itself could not be found, perhaps a photograph of it might exist?

In pursuit of that possibility, my search for the portrait had led me to the existence of an obscure, one-of-a-kind documentary album of the 1866 Special Exhibition of National Portraits. That album was held in the collection of Queen Victoria, for whom the unique book had been created as a special gift. Having made arrangements to examine this album at Windsor Palace early in my trip, I held the thinnest, most desperate hope that I might discover it contained a photograph of the room in which Richard Lane’s portrait had hung. If such a photograph had been taken, and was included in this album, I might thus obtain at least a distant, grainy glimpse of my Lost Lord Keeper.

Note: Turns out, I had been right. When I inspected it, I found the album did indeed include a fair photograph of the of the space that included the dividing wall upon which the now-lost portrait was displayed. Although appearing at a distance, and characteristically grainy for photography of that period, it had been well-taken. My gamble had paid off–that image of the portrait within a gallery would have been much better than nothing…if that’s all I’d have had.

However, the bored fates who seem generally to derive much amusement from taunting me had apparently decided to help we with a major “win.” As I was finalizing my analysis of the Woolnoth painting, I was stunned to receive an email containing an image of an old photograph of Richard Lane’s portrait as it hung in the 1866 exhibition. It was black and white, and affected by poor lighting and glare. But there he was! And he was a good match for the dramatically enshadowed character in the foreground of the nine-foot-wide 1844 Woolnoth painting, “The Trial of Strafford.”

Analysis of the Trial Managers

In the first two installments of this analysis (as presented to the staff of the Office of the Curator of the Parliamentary Art Collection at Westminster in April of 2018) we reviewed the accused, the royals, the judges, the nobles, and other minor actors in this dramatic scene. Not yet discussed are the opposing teams of the prosecution (the trial managers) and the counsel for the defense.

Because the judges were not as well documented historically (and because no original index of the painting has survived), the identification of many of the judges cannot be asserted with confidence. But the membership of the committee created to manage the trial was another story. These men’s roles were very well documented in the parliamentary records, and so were well known to the painter Thomas Woolnoth in 1844. In the image of the painting below, everyone except the members of the prosecution has been masked out to allow us to focus on this set of individuals.

In the existing research information about the painting provided in the Parliamentary Art Collection’s “online exhibition” of this painting, only the group at the far left of the painting were identified as trial managers. But if we look more closely at the clothing they are wearing (velvety brown with a green or blue sash and a wide white collar), we notice that similar attire is worn by those outside the low wall separating the floor from the galleries on each side.

This same style of dress is shared by the leader of the prosecution, John Pym, who is speaking. Pym is an excellent example of an individual whom Woolnoth depicted from a drastically different angle than he appeared in any of the portraits Woolnoth had available to him. The clarity of Pym’s depiction is remarkable and shows how effectively the artist used apparent lighting to draw the eye to the central moment of the scene. The artistic strategy of highlighting Pym is enhanced by Woolnoth’s use of shadows to suppress fields of the scene that were periphery to the moment of accusation at hand.

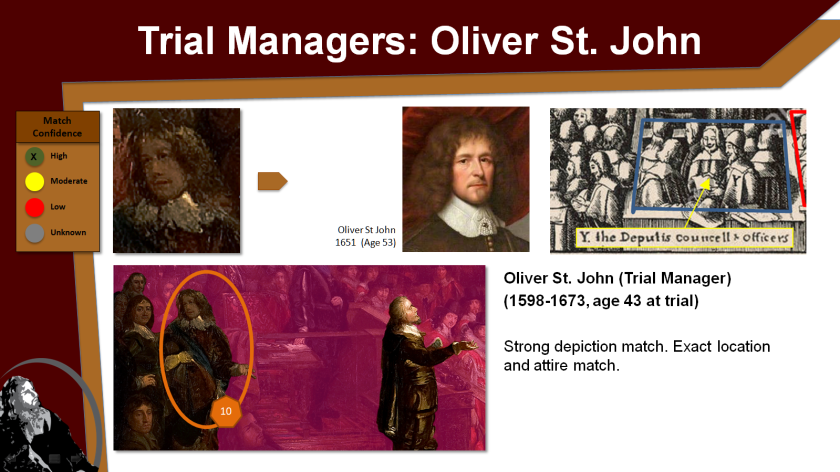

Behind Pym are the members of the prosecution present on the floor of the trial. The first of these is Oliver St. John. He was an interesting character, and is easily identifiable in the painting.

It was Oliver St. John who attempted to respond to Richard Lane’s dramatic applause concluded address to the court at the end of the trial. Edward Hyde (an important contemporary and author of the famous “History of the Rebellion”) denounced St John’s response speech as the most barbarous ever uttered in the House of Commons. St. John argued that, like beasts of prey (e.g. foxes and wolves), certain characters deserved no protection of the law, and were too dangerous to live. The obvious, fundamental flaw of St. John’s argument is that it relies on opinions and not evidence to discern such figurative wolves for destruction. I consider it evidence of the dark compliance of this particular parliament that St. John felt comfortable voicing such an argument there.

Behind St. John and nearly hidden at the far left of the scene is a depiction of Sir John Maynard. Like Richard Lane, Maynard came up through Middle Temple and was later elected Bencher there. A lawyer and an “adaptable” politician, Maynard managed to survive and even thrive throughout the seesawing political transitions of the middle through late 1600’s. At the time of the trial, Maynard was a vocal opponent of Strafford, and was apparently elated when the bill of attainder was passed. Much later in his career, he appears to have suffered a convenient lapse of memory concerning specific aspects of his participation in the trial when he was challenged about it.

Although his depiction is quite dark, Woolnoth did a good job of using the unique shape of Maynard’s head and facial features to capture a recognizable image of him in the scene.

Depicted in front of Maynard was Lord George Digby–another fascinating character among the Trial Managers. Although initially zealous in his prosecution of Lord Strafford, he changed sides after the impeachment failed, and actively opposed the bill of attainder under which Thomas Wentworth (Lord Strafford) was ultimately executed.

In the civil war that followed, Digby ultimately took the royalist side, but seemed to careen from one inept adventure and intrigue to the next–his efforts often hurting the royal cause more than they helped.

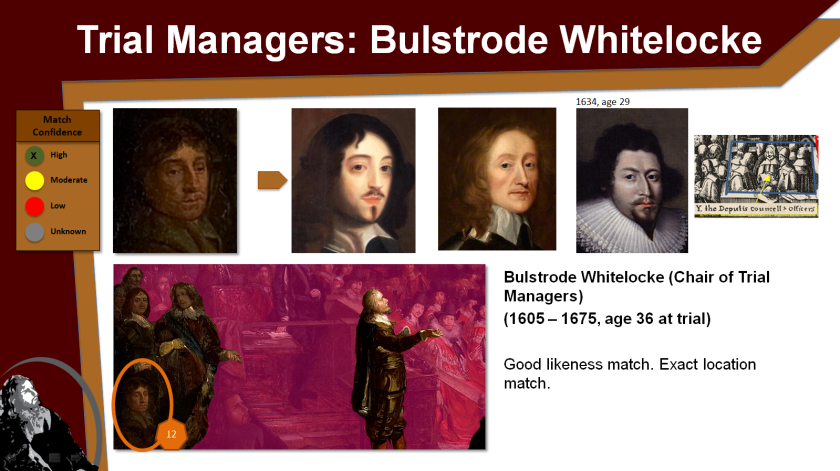

Seated in front of Lord Digby is the man who continually re-appears in the story of Richard Lane: Bulstrode Whitelocke. Unlike Lord Digby, there is a sense of continuity in Whitelocke’s trajectory. He was the chairman of the committee charged with the prosecution of Thomas Wentworth for treason.

Once described as an “intimate friend” of Richard Lane, Bulstrode’s heart was never with the royalist side. Rather, he seemed a capable man who walked a line that allowed him to be respected on both sides of the argument. Rising with the victorious Parliament in the civil war, he would later become Ambassador to Sweden and Commissioner for the custody of the Great Seal of the Commonwealth.

Given his relative prominence in the rebellion and the Commonwealth government that followed, it is surprising that Bulstrode Whitelocke was not among those whose heads were fitted to tall poles on the roof of Westminster Hall after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Whitelocke seems to owe his escape primarily to his relatively moderate behavior during the rebellion and more importantly, to the intercession of his friend and fellow Middle Templar, Lord Clarendon Edward Hyde. By the time of the restoration, Hyde (a staunch royalist who had endured exile with Charles II) had been appointed the third Lord Keeper to King Charles II. In this honored position (first held by Sir Richard Lane until Lane’s death in Jersey a decade before), Hyde was able to successfully intervene–downplaying Whitelocke’s participation and thus saving his life. Instead, Whitelocke was saddled with an insurmountable fine (of £10,000) and allowed to live out a quiet retirement in the countryside. There, Whitelocke spent his time writing respectfully balanced accounts of the rebellion in his memoirs.

The remainder of the Prosecution

The last member of the group of prosecutors behind Pym is William Strode. This appears to be the correct name of a the trial manager identified in some historical records as Walter Stroude. During the trial of Strafford, it was William Strode who proposed that Lord Strafford’s defense counselors (led by Richard Lane) should be likewise charged with treason simply for agreeing to defend him.

Strode was an adamant opponent of King Charles I who had spent 11 years imprisoned for his political opposition to the king in the period proceeding the rebellion. When he died in 1645 (during the Civil War), he was honored with a burial in Westminster Abbey. After the restoration, however, King Charles II ordered his body disinterred and thrown into a pit with the remains of 20 other lesser leaders of the rebellion.

Strode’s depiction in the scene is a good likeness match, but is somewhat dark, making it difficult to distinguish the color of his hair. Given his general similarity of appearance with a few of the other trial managers, I didn’t feel I could objectively assert his identification with more than “moderate” confidence.

The last member of the prosecution team depicted on the floor of the trial is Geoffrey Palmer. Like Richard Lane, Palmer was a Middle Templar from Northamptonshire, though he was 15 years Lane’s junior. Although he served as a trial manager in the prosecution of Strafford, Palmer was an MP who supported the position of the king at other times, and became a royalist during the Civil War. Like Richard Lane, he served King Charles in Oxford, where he was named the Solicitor General in 1645.

Following the surrender of Oxford, friends in parliament helped Palmer succeed at compounding for his estate (suffering a relatively moderate fine of £500). This allowed Palmer to spend the commonwealth years quietly practicing law in London. Following the Restoration, Palmer supported the prosecutions of the regicides (those chiefly responsible for the trial and execution of King Charles I), and was made a Master of the Bench in Middle Temple.

Despite the strong intuitive visual match, I grudgingly downgraded the identification of Geoffrey Palmer to “moderate” because this figure is depicted facing mostly away from the viewer, and also due to Palmer’s basic descriptive similarity to several other trial managers (i.e. Clotworthy and Hampden).

Depicted outside the railing separating the floor from the galleries, John Clotworthy was another Trial Manager who had an odd trajectory through the events of the day. His passion seems to have been religious fanaticism. Despite expressing a deep hatred for Lord Strafford during the trial, Clotworthy helped facilitate the Restoration nearly two decades later. Having thus found favor with King Charles II, Clotworthy was ultimately made a Viscount in Ireland.

The depictions I have identified as Clotworthy and Hampden could not be given higher than moderate confidence simply because the men were so similar in appearance, and their depictions are not as distinct as others in the scene.

John Hampden was a remarkable and highly principled figure who is remembered today in a ceremony where the door to the House of Commons is ceremonially slammed in the face of authority attempting to intrude into the affairs of the House.

During the Strafford trial, it seems Hampden was a critical voice supporting the decision to allow Strafford’s counsel (led by Richard Lane) to be heard at the end of the trial. Ironically, some evidence exists that a breakdown in support for the trial was averted by this action–had Richard Lane been prevented from speaking, the whole effort might have come to an end under a cloud of illegitimacy that might have made pursuing a bill of attainder an untenable tactic.

The Missing Member of the Prosecution

In my efforts to find images of all of the trial managers, there was only one person I could not find a likeness of: Sir Walter Earle (or Erle). His involvement in the trial is well documented, and the general details of his life seem a matter of clear history available to the painter, Thomas Woolnoth.

Despite a determined search for an image of Sir Walter Earle, I was unable to find a portrait, monumental effigy or any other likeness of him. Having accounted for all of the other trial managers, there remains one figure in the scene wearing the same apparel, but who has been depicted with his back turned to the observer. It is my theory that like me, Thomas Woolnoth was unable to find a portrait of Earle, and so cleverly positioned him in a way that did not require the depiction of his face.

Henry Vane, and the Ultimate “Karmic” Payback

Part of the work of my study was the identification of key players in the trial. There is one key witness for the prosecution in the trial whose role was so critical and well documented, I simply can’t imagine Woolnoth would have left him out. Sir Henry Vane (the younger) was a Member of Parliament (MP) who did not have any official duties in the trial, but whose contribution was the pivotal factor leading to the execution of Thomas Wentworth.

Vane’s father, Sir Henry Vane the Elder, was a member of the king’s Privy Council. A copy of his father’s notes from a privy council meeting a year before included a statement which Vane had attributed to Thomas Wentworth (Lord Deputy of Ireland at the time). In this statement, Wentworth suggested to King Charles I:

“…you have an army in Ireland with which you may reduce this Kingdom.”

In the trial, the prosecution’s interpretation held that Wentworth was urging the King to use the army of Ireland to subjugate England (note: in this usage the term “reduce” means to conquer militarily). Historians generally agree that it is quite likely this statement was deliberately interpreted out of context, and that it is more likely Wentworth was talking about the subjugation of rebellious forces in the kingdom of Scotland (another of the “three kingdoms” ruled by the monarchy).

Unfortunately for Wentworth, he had made a bitter enemy of the elder Vane. The two men were locked in a deep animosity that began when Lord Strafford denied Henry Vane an important title he had a right to. In his “History of the Rebellion,” Lord Clarendon (Edward Hyde) commented that this was an act of “the most unnecessary provocation…and I believe [resulted in] the loss of [Wentworth’s] head.”

Although the King had ordered Vane’s original notes containing the damning quote destroyed, Vane’s son (Henry Vane the Younger), later produced a copy of them, which he gave to the prosecution. When Strafford’s friends (likely including his lead counsel, Richard Lane) questioned the elder Vane about the meaning of his notes, Vane refused to clarify. Many feel that Vane was happy to allow the prosecution’s interpretation to lead to the destruction of his personal enemy, Thomas Wentworth.

Although the prosecution’s interpretation of these notes was insufficient evidence during the trial, the subsequent bill of attainder did not require the same standard of proof. In that process, the prosecutions assertion was all Strafford’s enemies needed to place his head on the block.

I was able to find clear portraits of both Henry Vane the Elder and Younger without issue. But the depiction I expected to find in the scene wasn’t apparent until I came back to a figure I had noticed but hadn’t seen as significant at the time. He lies on the very rightmost periphery of the painting, outside the railing separating the participants in the trial from the observers. On reflection, I realized since Sir Henry Vane was a member of the House of Commons, and not part of the trial (which was held in the House of Lords), he would have been allowed on the floor during the trial. His depiction at the periphery of the trial was also appropriate, since his involvement was indirect.

Owing to the murkiness of Vane’s depiction (which is partially clipped by the shadow of the painting’s frame in the photograph I used for my analysis) and the possibility Woolnoth might also have chosen to depict Henry Vane the Elder, I could not rate his identification any higher than of “moderate” confidence.

Counselors for the Defense

Once the prosecution team has been accounted for in the scene, only a single unexplained depiction remains. Interestingly, historical records indicate four men were appointed to serve as legal counsel for the defendant, including their lead, Richard Lane. However, I was unable to find portraiture of the other defense counselors. I suspect that the artist, Thomas Wentworth, had the same difficulties finding portraiture of them as I did, and chose to represent the defense with the depiction of a single person: the lead counselor, Richard Lane.

As I have previously described, the identification of Richard Lane in this scene is supported by a number of factors including the book he is holding (which seems to identify its holder as a legal scholar), by his seeming isolation from the trial managers around him, and by the stare of contemplation he is subjected to by the chairman of the trial managers (Bulstrode Whitelocke), who is seated behind him. This figure’s clothing is not consistent with the attire of the trial managers, in color nor in style. In fact, his clothing bears no resemblance to any official attire, yet he has been clearly depicted as a participant by his placement within the floor of the trial.

In the analysis slide of Richard Lane (just above), you can see the photograph I obtained of his portrait from the 1866 exhibition. Although the figure depicted in the scene is murky and presented in a dramatic pose, the figure’s long dark hair, high forehead, strong nose and chin beard are all consistent with the portrait of Lord Keeper Richard Lane!

At the end of my presentation appeared this “thank you” slide to Rhonda Martinek (my volunteer graphic artist), and includes some of the graphics she has created in support of this project. The design of the slides in this presentation were her doing, as were the powerful images of the painting with various groups isolated from the scene with color masks. I very much appreciate her efforts in helping me deliver such an effective presentation of this work!

——

Your comments and corrections are gladly welcomed. I admire great writing, but have little choice but to approach this task as one of grinding a workable edge onto a rough blade – with my thanks for your generosity of spirit and firm critique in the meantime!

–-Greg Sherwood

Thanks, bro! Another good article. I made a few polishing edits. There could be a couple more, but nothing earth shaking. As always, the sprinkling of levity throughout your writing is very effective. I love this adventure through history. Your work still blows me away. Congratulations!Suz

Sent from my Verizon, Samsung Galaxy Tablet

LikeLike

Hi Greg, You have been busy! I guess by now you will also have seen your article in the SJ Bulletin. Your work is a welcome contribution to expanding knowledge of the events of those momentous times.

I’m sure that one day, that portrait will turn up… it needs dedicated family history research, including Wills and inheritance, and property moves. I think Anna could do it, but she is probably doing other things in London, altho’ not working since her move there. You need to encourage her!

I trust you are well, and wish you a Happy New Year – and maybe a future return visit? very best wishes, Sue

________________________________

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greg, your research and passion for this project are incredible! I hope that if you ever put this historical mystery to rest, that you will pursue others.

LikeLiked by 1 person